—Is our problem lack of knowledge or what we know?—

There is a long tradition in the historiography of science and technology, and indeed in STS, of complaining that we know little about the relations of knowledge, technical practices and society. Indeed, Bruno Latour has suggested that, in modernity, such ignorance is a functional feature which made possible the transformations central to it. There is much of interest in such a thesis, which has more than a whiff of Austrian economics about it. But too often it is wrongly interpreted to mean that the problem we have is ignorance. From that analysis follows the injunction to start from scratch, to write histories following the scientists and engineers, and ignoring existing stories.

A related response is to say that our accounts of ‘science’ and ‘technology’ in history, not least in global history, are fatally flawed theoretically. They are, it is routinely claimed, Eurocentric, technologically determinist, embody assumptions about the ‘linearity’ of innovation, are ‘diffusionist’ and so on. Such criticisms pepper work in the field, but are highly problematic. The irony is that the histories which result from this critique and the consequent ignoring of the substantive conclusions of previous work are, far too often, themselves Eurocentric, technologically determinist, diffusionist, and even show secret devotion to the linear model!

Connecting continents through aviation in the 1950s. In the picture, BOAC poster, 1953, a year in which nearly all BOAC flights were by piston-engined aircraft. Wikimedia.

We need a better way of thinking about and rewriting the global history of those mysterious things called ‘science’ and ‘technology’. For the problem is not ignorance, nor primarily weaknesses in theoretical orientation, but something more basic. It is a lack of criticism and knowledge of what we think we know. For to avoid repeating misunderstandings we need to understand our understanding. What we need to grasp are the substantive empirical claims made, and the hidden framing assumptions which underpin them. Generally we need to read much more critically, and engage not with invented straw people and imagined hegemonic positions, but with good work taken seriously. We need to read the work of historians of science and technology for their substantive arguments instead of categorising past work as either methodologically flawed or advanced. We need to ask about the deep historiographical assumptions historians make, how useful they are, and why they are made. We might ask for example why so much global history is focussed on trade and communication or on ‘circulation’. Why is so much global history of ‘science’ or ‘technology’ concerned to assume radical difference between colony and metropole? How and why does it assume we know the history of the Eurocentre?

Getting to grips with these issues requires understanding of two forms of literature. The first is a proper understanding of what historians of science and technology have actually claimed. The second is the academic literatures outside the history of science and technology, and also popular understandings over time (what I call ‘historiography from below’). For our culture is suffused with stories about how ‘science’ and ‘technology’ have changed the world, which scientists and engineers, and the histories of science and technology who follow them, are apt to repeat too uncritically, as both celebration and condemnation.

We might for example begin to notice that the problem with such stories is not primarily that they are technologically determinist, Eurocentric or diffusionist or linear. There is a prior, graver problem, not least for not being known. Most technologically determinist arguments get the determining technology and the effect wrong; most Eurocentric theories are wrong about the Eurocentre, and most diffusionist studies are not in fact diffusionist, and the linear model was never put forward as a serious theoretical or empirical proposition. It would be wonderful to find a proper technologically determinist account, which gets the Eurocentre right, which is properly diffusionist, and defends a serious linear model. Such works would be worth arguing with. But we don’t have them.

Take the following case. For many historians of the period since the 1880s there was a foundational Second Industrial Revolution at the end of the nineteenth century, and perhaps subsequent revolutions too. But what if these have no empirical basis, focus on arbitrarily chosen novelties, and misrepresent the material constitution of the world? We need to understand that, not merely that these theories are technologically determinist.

Industrial Revolutions laid out for an academic audience. Source: Siekmann, F., Schlör, H. & Venghaus, S. Linking sustainability and the Fourth Industrial Revolution: a monitoring framework accounting for technological development. Energ Sustain Soc 13, 26 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13705-023-00405-4.

Many historians assume that we have a good account of the ‘sciences’ and ‘technologies’ of North America or Europe in the twentieth century but that this Eurocentric understanding does not apply elsewhere. But, is our account of the ‘sciences’ and ‘technologies’ of the Eurocentre in fact adequate? I don’t think it is, not least because of its reliance on industrial revolutions, and because, to explain my putting ‘science’ and ‘technology’ in quote marks, ‘science’ tends not to be scientific knowledge, but scientific research, primarily in the academy, and on academic particle physics and molecular biology in particular. And ‘technology’ does not mean either the material constitution of the world or techniques, but rather a very selected list of novelties at the beginning of their lives.

There are other large scale ideas which are prevalent, both in popular and academic writing which make important claims. Take the enduring cliché, in which the current new technique has globalised the world, bringing people together, or is so destructive it will ensure world peace. Thus in their time, the steamship, the aeroplane, the radio and television would create a peaceful ‘global village’. The bomber, and then the atomic bomb would create perpetual peace. Put like this the theories sound absurd, but they were put forward seriously and elements have been taken as descriptions of reality by historians and others, not least in global history and histories of international relations.

Bombers bringing peace to the world as envisaged in 1936. In the picture, the international air police from the film Things to Come (1936). Roger Russell’s website.

How do counter and understand such arguments? Well, we should study their history, in both academic and popular works. How did scientists of the past think about the relations of science and war? Well, they tended to repeat liberal cliches about the distance-eliminating and peace-creating effects of new systems of communication (which helps explain the prevalence of communication and exchange in global histories). Where did the idea that the atom bomb would create a new world come from? Not from scientists, but a long tradition of hailing the latest weapons as capable of changing the nature of war and peace. The arguments for the atom bomb were the same as those used just before for the bomber aeroplane. Wars remained stubbornly present, and they involve not only electronics and aeroplanes, but artillery and rifles, infantry, sailors and airmen, but this did not affect the dominant conceptual framing.

Or to take another case. Where does the idea come from that our globe has undergone a series of energy transitions, and which has powerfully influenced STS, come from? The answer is from nuclear scientists, and it has been sustained by many generations of energy procrastinators. But there has never been an energy transition overall, the process has been one of addition and symbiosis, so that more wood, and coal and oil is exploited today than ever before.

The transition model of energy history as a tool for thinking about the past and future. Energy transitions: the geological story | The Geological Society Blog.

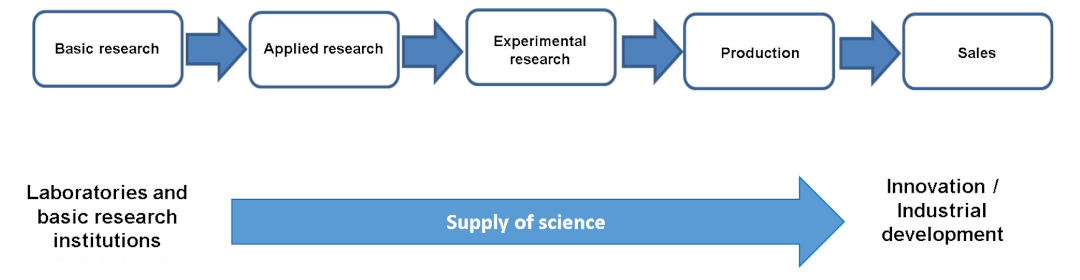

We can also apply this method to the work of historians of science and STS students. We can discover the moment in which scholars invent the idea that everyone before them believed in something very vaguely described as a linear model of innovation, when no such model was ever seriously proposed by anyone. We can also discover the moment when historians of science started complaining about supposed diffusionist histories of global ‘science’ and ‘technology’ and how they relied on citation of two or so works which were not diffusionist, and failed to establish that diffusionism (whatever that meant) was in fact dominant.

The linear model of innovation – the butt of nearly all articles on science policy, which nevertheless focus on the basic and applied end of the chain. Source: Leal, C. I. S. & Figueiredo, P. N. Technological innovation in Brazil: challenges and inputs for public policies. Rev Adm Publica 55, 3 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-761220200583.

In the above I have in effect argued that we are far too blind to the historiographical assumptions and empirical problems with our accounts of knowledge and the material in the global history of the twentieth century. Which leads to this methodological thought. Instead of assuming we know the Global North and have been ignorant of the Global South, let us study the South and assume, not difference from the North, but rather than what we discover about the South is more likely to be true for the North than much of understanding of the North suggests. For in the North as much as the South is a place where scientific and technical novelties generally come from elsewhere, as do most machines, where most people and institutions are imitators, not innovators, and imitate the old as well as the new, where maintenance is fundamental to technical objects, where students of science and technology mostly chemistry and engineering and medicine, and not molecular biology or particle physics. In short, our implicit models of the North should not be taken as adequate. Turning the world upside down is a very good way to understand this.

David Edgerton

Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine, History Department, King’s College London

How to cite this paper:

Edgerton, David. The Global History of Science and Technology. Sabers en acció, 2025-05-07. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/the-global-history-of-science-and-technology/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Recommended reading

David Edgerton, The Shock of the Old: Technology and Global History since 1900 (London, 2007) trad. Innovación y tradición. Historia de la tecnología moderna (Barcelona, 2008).

David Edgerotn, ‘Time, Money and History’, Isis, Vol. 103, No. 2 (2012), pp. 316-327

David Edgerton, ‘Innovation, Technology, or History: What is the Historiography of Technology About?’, Technology and Culture Vol. 51, Number 3, (2010), pp. 680-697.

Studies

Edisson Aguilar Torres, ‘Toward a Symmetrical Global History of Technology: The Adoption of Chlorination in Bogotá, London, and Jersey City, 1900–1920’, Technology and Culture 65 (4) (2024): 1195-1221.

Ralph Desmarais, ‘Jacob Bronowski: a humanist intellectual for an atomic age, 1946–1956’, British Journal for the History of Science Vol. 45 (2012), 573-589 (2012).

Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, Sans transition: Une nouvelle histoire de l’énergie, (Paris, 2024), trad. More and More and More: An All-Consuming History of Energy (London, 2024) trad. Sin transición. Una nueva historia de la energía (Barcelona, 2025)

Hermione Giffard , ‘Narrative Disconnect: Where do our ideas about invention come from?’, History and Technology (forthcoming)

Ernst Homburg, ‘Chemistry and Industry: A Tale of Two Moving Targets’, Isis 109 (2018), 565-576.

Thomas Parke Hughes, American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm, 1870-1970. New York, 1989.

Steven Shapin, The Scientific Life. A Moral History of a Late. Modern Vocation. Chicago, 2008.

Galina Shyndriayeva, ‘Musk and the Making of Macromolecules: Perfumes and Polymers in the History of Organic Chemistry’, Isis 115 (2024), 292-311

Waqar Zaidi, Technological Internationalism and World Order. Cambridge University Press, 2021.