—Insights on technological change from the city of Madras in early twentieth-century India.—

As David Edgerton has pointed out in the introduction to this section, water filtration is not a technology that comes to mind when we think of globalisation. Yet it was a profoundly global technology in the early 20th century. As late nineteenth century urbanisation began to stretch the capacity of pre-existing living arrangements, overcrowded habitations and increased pollution of local sources of water supply became commonplace in many industrialising cities of the world. Combined with the growing integration of the world through trade, transport, and imperial conquests, these situations provided the perfect conditions for the spreading of devastating epidemics such as cholera. As epidemics became a global problem, solutions to them also took a global scope, and water filtration was one of the suite of solutions advocated by sanitary reformers of the late nineteenth century. Cites across the world adopted this technology almost simultaneously with the early decades of the 20th century forming a crucial period.

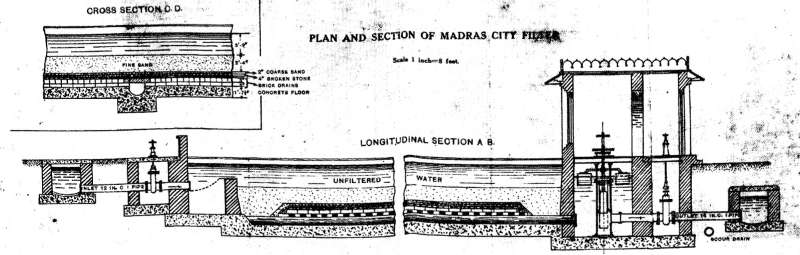

The history of filtration leading up to the early 20th century was one of gradualism. One of the earliest cases of documented use of water filtration in the 19th century was in Paisley in Scotland in 1804, global attention to the practise began to emerge after London’s Chelsea waterworks company introduced it to purify its water supply in the 1820s. At a very generic level, these filters, called slow sand filters, consisted of shallow open tanks where water was passed through three layers of filtering materials: gravel at the bottom, a layer of coarse sand in the middle, and a layer of fine sand at the top.

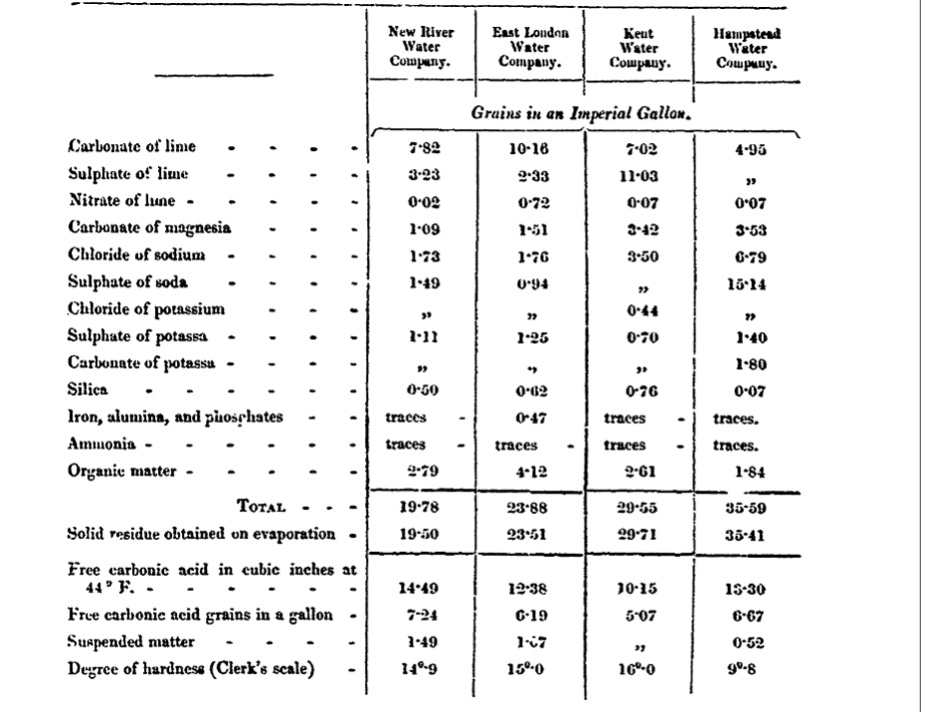

A water analysis table in the pre-bacteriology era from London. Source: Report of the Government Commission on the Chemical Quality of Supply of Water to the Metropolis, 1851.

The adoption of this technique in the initial decades was initially gradual because of two main factors. One, in the mid-19th century there was little consensus on whether water was the medium through which diseases such as cholera were spread. The then prevailing paradigm of disease causation, labelled the ‘miasmatic’ paradigm of disease, held filthy environments, rather than contaminated water, caused such diseases. Two, it was unclear to the city authorities, as to what was it that the filters were purifying. Between 1830 and the mid-1880s, water filtration was used to ensure the chemical rather than the bacteriological purity of water, and it was felt that they contributed to better sight and smell of water, more than any perceived safety from contaminants in water

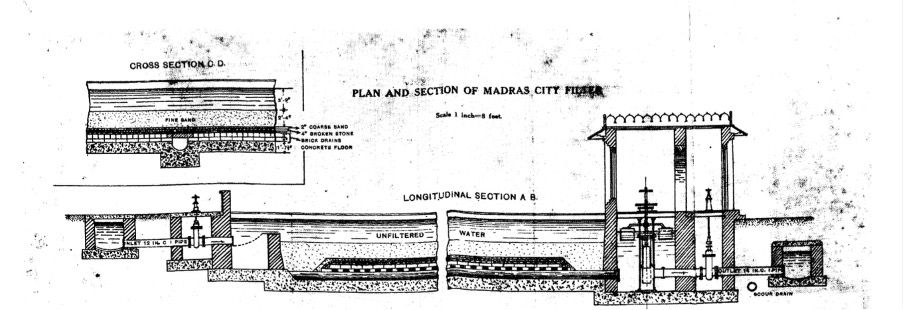

Illustration of the Madras Slow Sand Filters. Source: Note by Special Engineer of Madras Waterworks, 1918.

Three important developments changed the role and importance of filtration from the 1880s onwards. Firstly, the research insights from scientists such as Koch, Louis Pasteur, etc., led to an understanding that diseases were caused by microbes, rather than filthy environments inaugurating the emergence of the germ theory of disease. Secondly, experiments conducted in London indicated that the slow sand filters were also effective for bacteriological control with the results showing that they could remove ninety-five percent of micro-organisms present in water. Thirdly, the spectacular success of slow filters in 1892 in bringing a cholera outbreak in Hamburg under control, provided practical demonstration of the bacteriological efficacy of filters, thereby making a strong case for the introduction of water filtration as a public health measure. As a result, water filtration and bacteriological analysis found enthusiastic backers among the medical practitioners with bacteriology becoming the cutting edge medical science of that period.

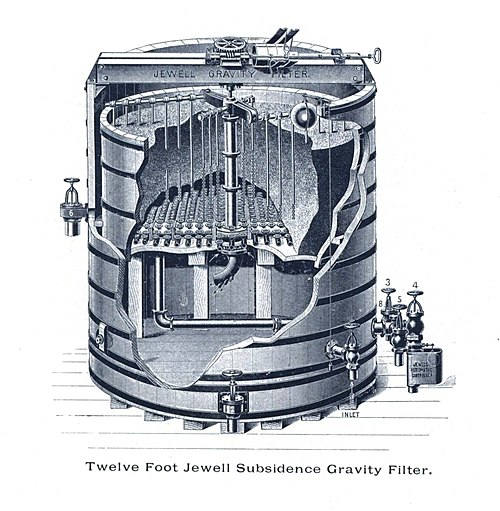

The global diffusion of water filtration technologies over the next three decades however was far from automatic. The key problem here was finding filtration systems that would suit the varied environmental conditions found in different parts of the world. Raw water that was available in one location markedly differed from that in another location, and therefore filtration method that was suitable in one location, was not suitable in another. American waterworks, for instance, began preferring a new method known as mechanical filtration as an alternative to slow sand filters arguing that the latter was unsuitable for their purposes. These pronouncements from American engineers were often inseparable from marketing and advertising claims of American engineering firms about the alleged superiority of mechanical filtration systems over the slow filtration systems.

Therefore, between 1890 and 1920, there was uncertainty about what method of filtration would suit what context, and several cities had the painful experience of implementing one system and realising that it was not the ideal one leading to heavy sunk costs. This had the inadvertent effect of undermining the legitimacy of the medical and engineering experts that were active proponents of the implementation of filtration, given that in those periods filtration systems were expensive capital goods that occupied a sizeable part of the expenditure on waterworks. It was not until the end of the first world war that comparative performance of rapid filtration and slow filtration could be evaluated as a consequence of the war time effort to obtain pure water from Nile by the British expeditionary campaigns in Egypt.

Cross-section of a Mechanical Filter Marketed by the Jewell Pure Water Company. Wikimedia.

The case of the Indian city of Madras gives an illustration of this trend. Madras, the third largest city in British India, the sixth in the British empire, was a thriving commercial centre in the early 20th century. The sanitary statistics of the city however belied its stature, indicating instead that it was one of the worst when measured in terms of deaths due to infectious diseases. The fact that the British saw Indian cities as disease prone did not mean much remedial action was taken until the early 1900s when a devastating plague epidemic stimulated action.

Madras city built a filtration plant in 1914 exactly at a time when there was a flux in the global landscape of water filtration due to the competition between the American (mechanical filtration) and British (slow sand filtration) methods. The British experts that were involved in the decision making in Madras, chose to follow the British precedent rather than implement mechanical filters, as in their view the American methods were untested. The city built slow sand filters at a substantial cost to the city’s tax payers, a majority of whom were Indians.

But soon it became apparent that the British filtration methods were not suitable for the Madras city’s water, causing serious anger among the city’s Indian elites. Coincide as this controversy did with the war-time political tensions in India between the British colonialists and Indian nationalists, the filtration debate became a politically charged subject . The inability of British engineers to build a functioning water filtration system became a local nationalist grievance and made its way into nationalist discourse around the demand for greater self-governance. With the controversy refusing to die down, the colonial government ordered an inquiry into identifying the most suitable method for filtering the city’s water. Between 1917 and 1925, a series of experiments followed wherein expert opinion shifted from favouring one method of filtration to another, before finally suggesting the use of mechanical filtration to purify the city’s water.

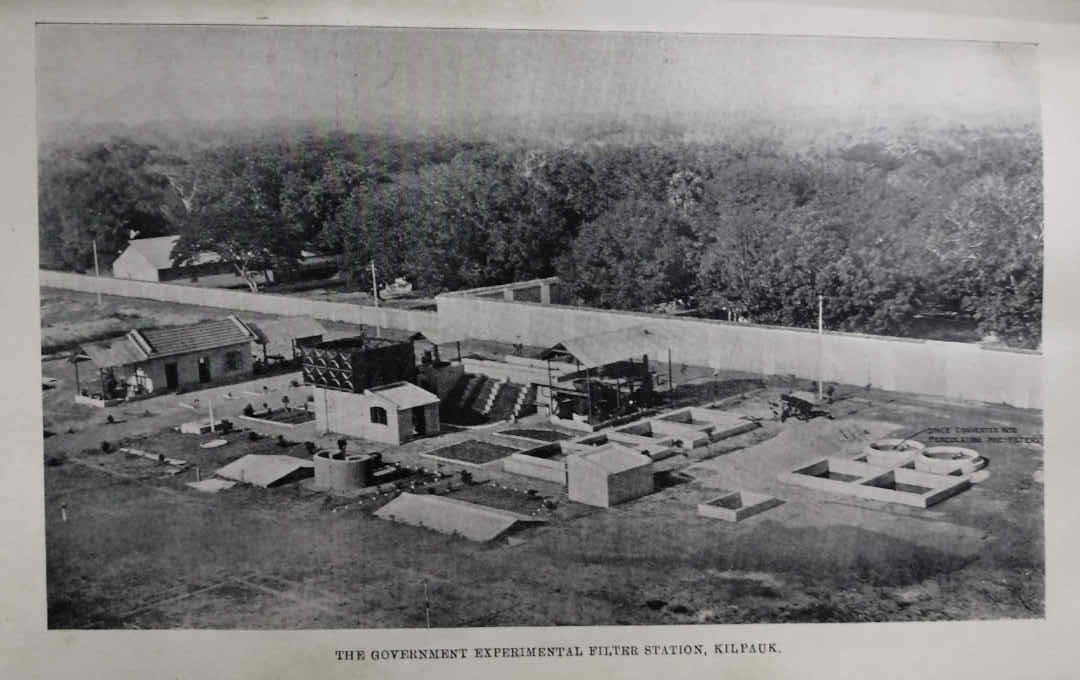

A Government Water filtration Experiment Station in Madras from the 1920s. Source: Report on the Experiments Conducted at the Government Experiment Filtration Station at Kilpauk, 1929.

Despite the results of the experiments, this was a step that the city’s political leaders were reluctant to proceed with. Aside from the costs that were involved in implementing this step, they were unable and unwilling to trust expert views on water filtration due to dissensions, disagreements on the subject in the previous years, and the failure of the slow filtration method which was the expert’s choice earlier. This led to a situation wherein the city did not implement the new recommendations and instead decided to continue using the older method.

Fortunately for the city, chlorination of water supplies had emerged as a cheaper solution for water sterilisation in the 1920s which the city adopted as an interim stopgap method to ensure bacteriological purity even as it made the ‘aesthetic’ aspects of water, such as taste and smell, undesirable. It was not until after the end of the second world war that the city eventually decided to try mechanical filtration methods when the latter’s functioning had become well understood.

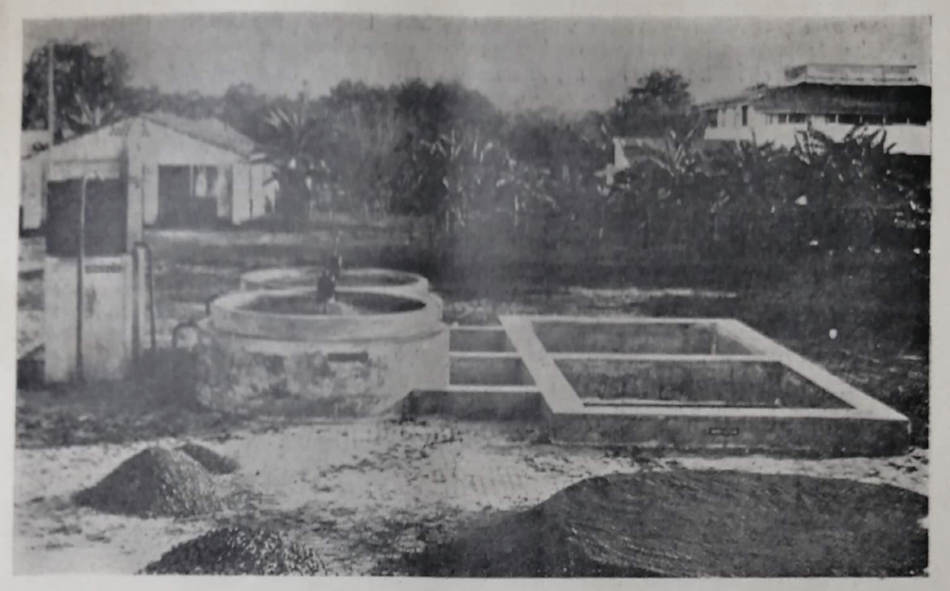

Filters used in Filtration Experiments in Madras. Source: Report on the Experiments Conducted at the Government Experiment Filtration Station at Kilpauk, 1929.

Madras’ adoption of water purification technologies in early twentieth century highlights two important aspects regarding globalisation and technological change. One, that imitation and transfer are important, but far from straightforward mechanisms in the global history of technology that require analysis and further problematisation. As David Edgerton has pointed out, the key issue in this history is what is chosen to be imitated, and why. Two, globalisation of technologies do not mean the production of homogeneity across the world. The circumstances of imitation, from the economic to the institutional can and do produce divergent histories of technological change and use. In the Madras case, the fact that the initial effort imitate British filtration methods had been a costly failure, weighed heavily on further considerations around what technologies to adopt and when; a dilemma that was not helped by a global technological landscape in flux as new filtration technologies began emerging on the scene.

Viswanathan Venkataraman

King’s College London

How to cite this paper:

Venkataraman, Viswanathan. The globalisation of water filtration. Sabers en acció, 2025-09-10. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/the-globalisation-of-water-filtration/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Recommended reading

Hamlin, Christopher. A Science of Purity: Water Analysis in Nineteenth Century Britain. Bristol: Adam Hilger, 1990.

Melosi, Martin V. Precious Commodity: Providing Water for American Cities. Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011.

Sedlak, David. Water 4.0: The Past, Present, and Future of the World’s most Vital Resource. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

Studies

Chakrabarti Pratik, “Purifying the River: Pollution and Purity of Water in Colonial Calcutta,” Studies in History 31, no. 2 (Aug 1, 2015), 178–205.

Chakrabarti, Pratik, Bacteriology in British India : Laboratory Medicine and the Tropics(Rochester, N.Y.: University of Rochester Press, 2012).

Evans, Richard, Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years (Oxford: Clarendon, 1987).

Ismail, Shehab, “Epicures and Experts: The Drinking Water Controversy in British Colonial Cairo,” Arab Studies Journal 26, no. 2 (October 1, 2018), 9–43.

Sharan, Awadhendra, “From Source to Sink: ‘Official’ and ‘Improved’ Water in Delhi, 1868-1956,” The Indian Economic and Social History Review 48, no. 3 (Jul 1, 2011), 425–462.

Sources

Baker, M. N. “Sketch of the History of Water Treatment.” Journal – American Water Works Association 26, no. 7 (Jul 1, 1934): 902–938.

Bunker, George C. “The use of Chlorine in Water Purification.” Journal of the American Medical Association 92, no. 1 (Jan 5, 1929): 1–6.

Madeley, J. W. “Town Water Supply in India.” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 77, no. 3966 (1928): 27–47.

McDowall, R. J. S. “The Water Supply of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, with Special Reference to the Efficiency of Mechanical Rapid Filtration with Chlorination.” Epidemiology & Infection 19, no. 3 (1921): 305–308.

Websites and other sources

“Documentary History of American Water-Works,” http://www.waterworkshistory.us/tech/Filtration.htm.

“Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History,” https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Category:Water_Purification.