—The passion for collecting wonders of nature led to the creation of an essential space for understanding the science of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries: the cabinet of curiosities.—

The passion for collecting that was unleashed in the courts – either princely, noble or ecclesiastical – of the Renaissance gave rise to the appearance of the so-called Wunderkammern (‘chambers of wonders’) or cabinets of curiosities, as Giuseppe Olmi’s researches revealed at the time. From the second half of the sixteenth century on, collecting was also adopted as a cultural practice of social prestige by other social groups. As the economic enrichment and power of these new groups (merchants, bankers, bureaucrats) grew, aristocratic cultural practices were adopted, such as maintaining a cabinet to house, study and exhibit its owners’ collections. As is often the case, on being appropriated by new groups, collecting was transformed according to their new interests, possibilities and particularities. Thanks to this transformation, many of these places became spaces for the creation and circulation of knowledge on nature, reaching a position of great relevance within the complex topology of knowledge and scientific practices of the early Modern Age.

Physicians and apothecaries were outstanding examples of these rising groups that ended up building for themselves, and for their closest cultural circle, a specific type of cabinet of curiosities: the nature cabinet. From the late sixteenth century and throughout the seventeenth century, dozens of European scholars were encouraged to create collections of specimens and objects from the three realms of nature (animal, plant and mineral). It was a question of gathering them in a limited space, where a reduced representation of the natural world was formed, that is, a specific microcosm. This commitment to recreating a world on the human scale of the cabinet sparked an ambition to understand the mechanisms of the creation of nature, captured in the existence of different plant and animal species and various geological formations.

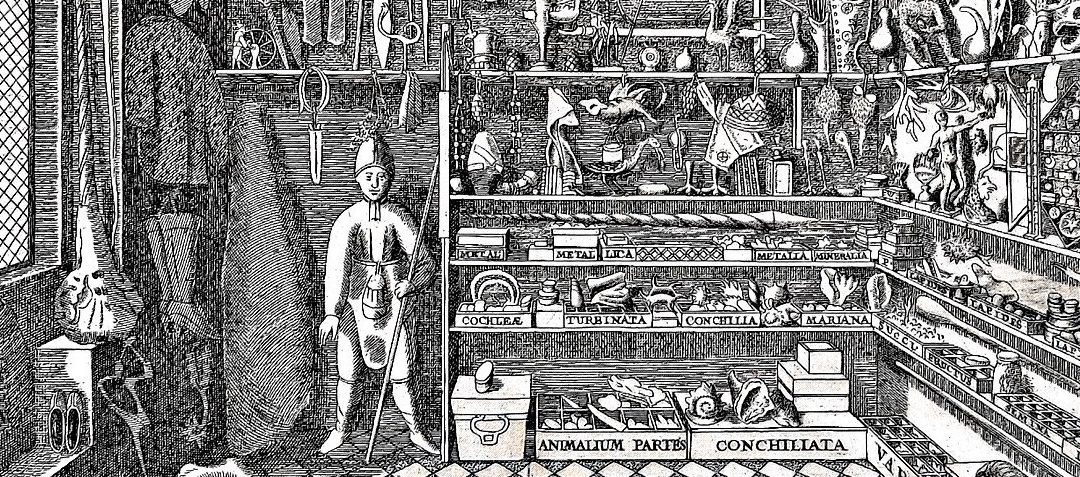

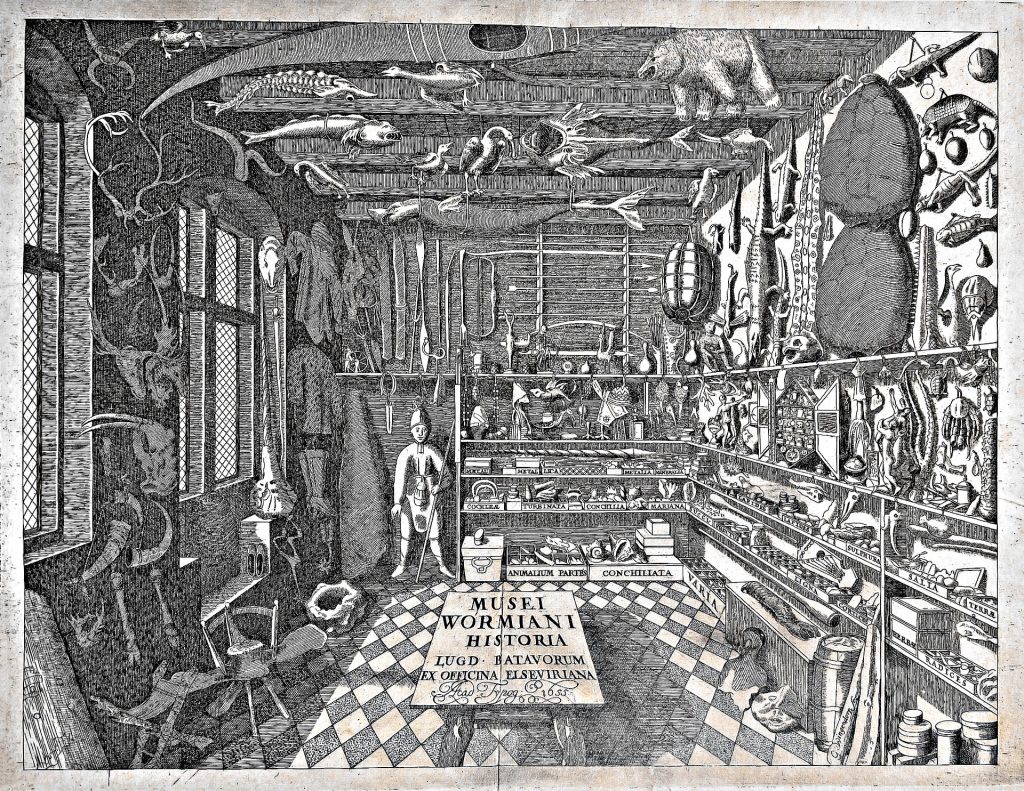

Thus, cabinets of curiosities progressively housed new and very different intellectual and material practices, although they were all closely related to the aim of scrutinising the products of nature to unravel their secrets. The cabinets of curiosities were, for example, the space for the development of the visual reproduction of plants, animals and minerals, in addition to research on various techniques to better conserve specimens (for example, dry herbariums for plants or evisceration and taxidermy for animals), and the various methods for their classification, nomenclature and labelling, and microscope observation and a long list of new techniques, often coming from artisan cultures and not precisely from the academic world.

Frontispiece of Musei Wormiani Historia showing Worm’s room of wonders. Wikipedia.

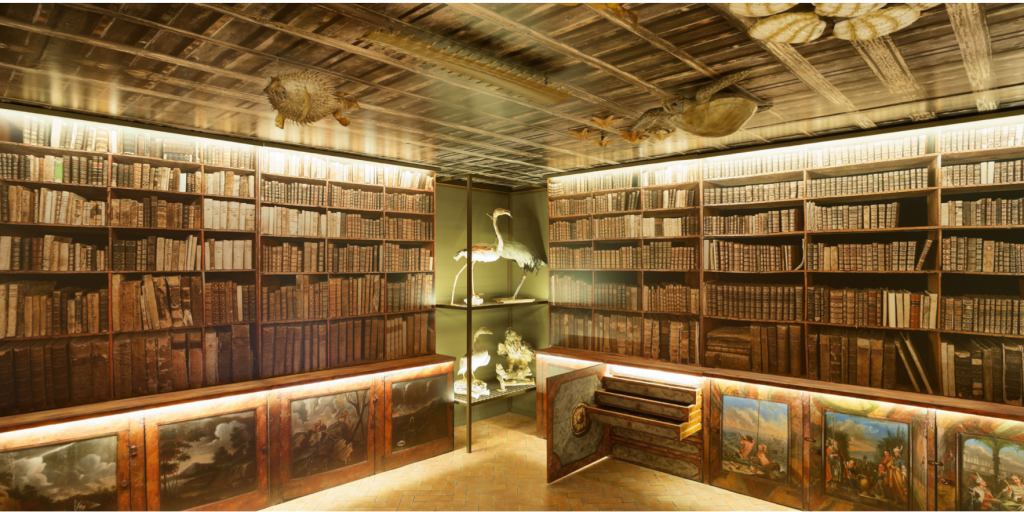

All this led to the cabinets of curiosities becoming the ideal urban space for experimental research on the natural world for more than two centuries. In fact, there is a record of cabinets in dozens of cities across Europe (and also in colonial cities in America and Asia) for over nearly three hundred years. However, many of these collections have been lost and others have become part of museum collections, which has blurred their boundaries and initial features. Nevertheless, there is much that can be reconstructed based on the catalogues published by some of their creators to publicise the collection (such as the case of Olaus Worm in Copenhagen or Francesco Calzolari in Verona), through the engravings of cabinets that appear in various scientific works (as in the case of Besler, in Nuremberg), through the correspondence of the time that has been preserved, and, above all, due to the survival of some of these cabinets in their almost original state, as in the case of the Francke family (father and son) housed in Halle or that which the Catalan family of apothecaries, the Salvador family, kept in the city of Barcelona for five generations.

It is important to emphasise that the cabinet, created in the private sphere (or even the domestic sphere), took on a new dimension which we must consider to be public or, at least, open to a certain class of public. Because, ultimately, visitors are the ones who gave prestige to the cabinets, their owners and the cities that hosted them; as the readers (alone or as listeners of public readings) were the ones who shaped the impact and effects of a certain scientific work. It is enough to observe some of the images that have survived to our time to realise that the cabinet, in its formal arrangement, was designed to be exhibited before real visitors or virtual visitors, who contemplated an engraving or painting of it. In other words, communication of scientific knowledge in the cabinet space was determined by a specific regime of exhibition that allowed the visitor and the owner to establish a particular exchange, while establishing implicit rules for the production and circulation of that knowledge, as well as for the contemplation and manipulation of the thousands of pieces that made up the microcosm of each cabinet.

Recreation of the original layout of the Gabinete Salvador (Barcelona), made for the temporary exhibition “Salvadoriana”. J. M. Llobet, Museu de Ciències.

In this sense, it must be kept in mind that it was first and foremost an orderly microcosm. Perhaps to our present-day eyes, the arrangement of the collection in most of the cabinets of which images have survived seems chaotic, due to the fact that our view has been shaped by another type of order. Although an effort must be made to understand it, those nature cabinets of curiosities had an order, for the development of which books played an essential role, but also the conditions of conservation, the material from which the objects were made, their geographical origin and their intended use for humans. It should be noted that the cabinet was the laboratory where most natural history was produced until the end of the Enlightenment. Natural History is specifically the paradigmatic science of the taxonomy, which involves naming, describing and classifying among its basic practices. It was one of the ‘ways of knowing’ according to the expression of the historian John Pickstone, features of the history of science in what has come to be known as Western civilisation. The ultimate ambition of classifying the materials brought together in the collection is nothing short of ordering the world, restoring it to its natural order. The idea of nature as the work of a Creator is inseparable from the conviction that scientific inquiry serves to unravel the Creator’s design and glorify His work by divining His laws. That is the ultimate function of the cabinet of curiosities. Taxonomic science began its most powerful stage at this time; as is well known, from natural history it would soon spread to medicine and, later, to other disciplines. Both readers of natural history books and visitors to the cabinets were involved in that development of the order of things.

José Pardo Tomás

IMF-CSIC

How to cite this paper:

Pardo Tomás, José. Nature in the cabinet. Sabers en acció, 2020-11-30. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/nature-in-the-cabinet/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Recommended reading

Marcaida López, José Ramón. Arte y ciencia en el barroco español. Historia natural, coleccionismo y cultura visual. Madrid: Fundación Focus-Abengoa, Marcial Pons Historia; 2014.

Margócsy, Dániel. Commercial Visions. Science, Trade, and Visual Culture in the Dutch Golden Age, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Olmi, Giuseppe. L’inventario del mondo: Catalogazione della natura e luoghi del sapere nella prima età moderna, Bologna: Il Mulino; 1992

Pardo-Tomás, José. Salvadoriana. El gabinete de curiosidades de Barcelona. Barcelona: Museu de Ciències Naturals-Institut Botànic de Barcelona; 2014.

Studies

Beretta, Marco (ed.). From Private to Public. Natural Collections and Museums. Sagamore Beach, MA: Science History Publications; 2005.

Bleichmar, Daniela; Mancall, Peter C. (eds.). Collecting across Cultures: Material Exchanges in the Early Modern Atlantic World. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2011.

Delbourgo, James. Hans Sloane and the Origins of the British Museum. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press; 2017.

Findlen, Paula. Possessing Nature. Museums, Collecting and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy. Berkeley-Los Angeles: University of California Press; 1994.

Marples, A.; Pickering, V. R. M. Exploring cultures of collecting in the early modern world, Archives of Natural History, 43 (1), 2016: 1-20.

Olmi, Giuseppe. From the marvellous to the commonplace: notes on natural history museums (16th-18th centuries). In: Renato G. Mazzolini (ed.). Non-verbal communication in science prior to 1900, Florence: Leo S. Olschki Publisher; 1993; pp. 235-278.

Pickstone, John. Ways of knowing: A new history of science, technology and medicine. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000.

Rey-Bueno, Mar; López-Pérez, Miguel (eds.), The Gentleman, the Virtuoso, the Inquirer: Vincencio Juan de Lastanosa and the Art of Collecting in Early Modern Spain. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2008.