—Received views and their limits in the history of agriculture, with illustrations from the United States and South Asia.—

Agriculture is central to our understanding of the modern world. Dominant historical models of the twentieth century, including our national histories, are informed by agriculture, or more properly, what is assumed to have happened to agriculture. The role of particular technological and scientific innovations, and forms of production, are central to these models. For instance, we are told that the success of Britain as the first industrial nation rested on its transition out of agriculture and the resulting surplus pool of labour in cities. A British Agricultural Revolution, between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, based on innovations in drilling, cropping, and livestock breeding, is credited with paving the way for this first Industrial Revolution. In the US, one dominant story is the industrialisation of agriculture in the early twentieth century centred on the Midwest, with mechanised farms resembling ‘mass production’ factories, a model which inspired apparatchiks in the Soviet Union.

The diesel-powered gin in Burton, Texas, is one of the oldest in the United States that still functions. Wikimedia.

In the poor world, and particularly India, a Green Revolution, or the application of high yielding varieties (HYV) of cereal grains, particularly wheat and rice, is said to have invigorated a dormant agriculture and transformed the subsistence-bound and traditional peasant into a modern capitalist farmer in the 1960s.

A term coined by the director of USAID in 1968 to contrast it with the social upheavals of “red revolutions”, the Green Revolution is often presented as a tale of heroic agricultural scientists and American philanthropists rescuing the poor world from mass starvation. Historians have challenged this popular narrative by situating the institutional networks (public and private) and scientific expertise within the context of Cold War US geopolitical strategy, emphasising the political construction of social scientific categories (for example, ‘hunger’), and the uneven impact on local societies of such social engineering. Historians have also debated the periodisation of this Revolution, with some pointing to antecedents in the early twentieth century in a Long Green Revolution, while others insist on a radical break in the 1960s or later.

But the Green Revolution is unique in being an agricultural revolution of the twentieth century, a century more commonly associated with successive industrial revolutions. However, even the Green Revolution is confined to the poor world. More generally, agriculture in the twentieth century is associated with poverty, subjugation, and the stagnation of the poor world, and its absence in histories of the rich world is taken to be a measure of progress or domination of the West, despite the presence of rich agricultural nations (we seldom hear of Green Revolutions in the US, Australia, or Argentina, for example).

Sifeng Model 12 HP 2WT with 5.6 tonnes of rice, Bangladesh. Wikimedia.

There is, to be sure, some truth to these models, but they are too neat and get important empirical details wrong. For instance, we now know that far from being vestigial to its modernity, agriculture in Britain radically transformed in the middle of the twentieth century, even more so than any previous period. Agricultural output grew at an annual rate of 1 per cent per annum between 1750 and 1860, the period of the ostensible British Agricultural Revolution, and it hardly grew between 1867 and 1934, while the annual rate of growth between 1945 and 1965 was 2.8 per cent. In gross figures, the volume of output tripled before the Second World War to 1981-85, from £4 billion to £12 billion (in 1968 prices).

In the US, the dominant form of farming for much of the century was not the farm-as-factory but the family farm, a global norm in this period. Indeed, the average US farm size was in fact larger in 1850 than in 1900, exceeding this level only in the 1950s, and even then, the US South notably bucked the trend. While US farms were larger than the global average, the trend towards bigness was a much more recent phenomenon.

Nor were peasants and agricultural labourers confined to the non-West periphery: the share of the labour force working in agriculture in 1950 was 37 percent in Ireland, 33 percent in Italy, and 57 percent in Poland, and in France, where Eugene Weber saw peasants becoming Frenchmen by the First World War, 23 per cent, or about one in five French, still lived in a peasant world in the middle of the twentieth century. The application of modern science and technology, and large farms, was similarly a global phenomenon, to be found in enclaves of the poor world as much as the rich, most notably in large Javanese farms adjoined to modern sugar mills and using coerced peasant labour. Similarly, small-plot sugar cultivation, far from being pre-capitalist or traditional, was embedded in new circuits of exchange and utilised new tools and production processes, notably in the colonos of Cuba and gur (unrefined sugar) production in North India.

Modern cotton gins in use in the US. Wikimedia.

Why do dominant historical models overlook these empirical realities? A clue lies in their underlying assumptions. One assumption concerns what is understood by agriculture or agricultural activity in our histories. Our models have a limited conception of agricultural practices and techniques, and when we speak about revolutions in agriculture, as in industry, we speak of particular scientific or technical innovations when it first appeared, rather than the widespread and global use of techniques, old and new.

Importantly, we tend to conflate agriculture with cultivation, or with activities done purely on the farm, and overlook the importance of auxiliary activities, like soil preparation, processing, preservation, irrigation, power, transportation, silage, storage, livestock breeding, marketing, and so on. We also tend to overlook physical geography, seasons and seasonality, and agricultural cycles and their impact on production. Another assumption is our restrictive definition of capitalist agriculture, typically associated with the appearance of free (i.e., waged) labour, of increasing concentration of land and capital, and with particular industrial models of mass production. These, as we have seen, are wholly inadequate.

Yet another assumption concerns our unit of analysis, which is often national or imperial. We seldom look below the national (or imperial) level, at the level of regions or individual farms, and the investment decisions of farmers, or above it, in a comparative assessment of different regional economies and state actions. As a result, we let our political contexts – whether nations, West or The Rest, Global North or South – dictate our understanding of agriculture when it should be the other way round.

What might a history of agriculture and agricultural techniques look like if we abandon these assumptions and standard models, and instead focus on use, imitation, agricultural practice, and beyond national or pre-given political geographies? Such a history will be alive to the uneven, but combined, development of global agriculture in the twentieth century, its heterogeneity, but also its similarities. It will be less stadialist, account for overlooked innovations, and can provide richer causal answers to global convergence and divergence in production and productivity. I will illustrate this briefly with examples of two widely adopted machines in regions in the US and South Asia: the cotton gin and the internal combustion engine.

A Rot-E-Taek hauling logs in Isan, Thailand. This is one of many types of two-wheel tractor. Wikimedia.

The cotton gin, a device used to extract cotton lint from seed cotton, was a peasant activity in colonial India and a plantation activity in the US South. These were divergent systems: in the Bombay Presidency, the largest regional producer of cotton, the woman of the peasant household utilised a hand-cranked churka or roller gin to manually clean the short-stapled local cotton following harvest season, while American mid-stapled cotton plantations, reflecting their settler inheritance, used draft animals, typically a horse or mule, and wooden structures to power the Whitney saw-gin, which was nonetheless labour-intensive in its use of slaves and slave mechanics.

The humble churka, however, did find selective use in the long-stapled cotton plantations on the US seaboard, but it was foot rather than hand-powered. By the interwar period, cotton ginning in both regions no longer took place at the point of cultivation, but in gin factories in large villages or towns, and was steam or diesel powered, with the cotton press following suit. In India, the ‘Macarthy’ roller gin used in these factories was an American innovation perfected by machinists in Manchester, the Platt Brothers & Company of Oldham. Peasant women operated Platt’s machines in predominantly Indian-owned factories which supplied most of its raw cotton to European and Japanese and domestic markets, not Lancashire.

This was far from an imperial story. Instead, it was a global story of convergence in the use of processing machinery, with British machine makers supplying the Macarthy gin in Egypt, parts of East Africa, and China. This history is written out of our accounts of global cotton and capitalism which stress dependency, imperialism, and de-industrialisation in India instead of the emergence of a massive raw cotton export industry. While US ginneries adopted flow production and became larger in scope and less labour-intensive by the 1940s, in India these systems were adopted in the 1960s, with ginning machines now produced by Indian firms. China and India today are the largest producers of cotton, with the US coming in third. Freed from our models, we are better placed to explain this turn of events.

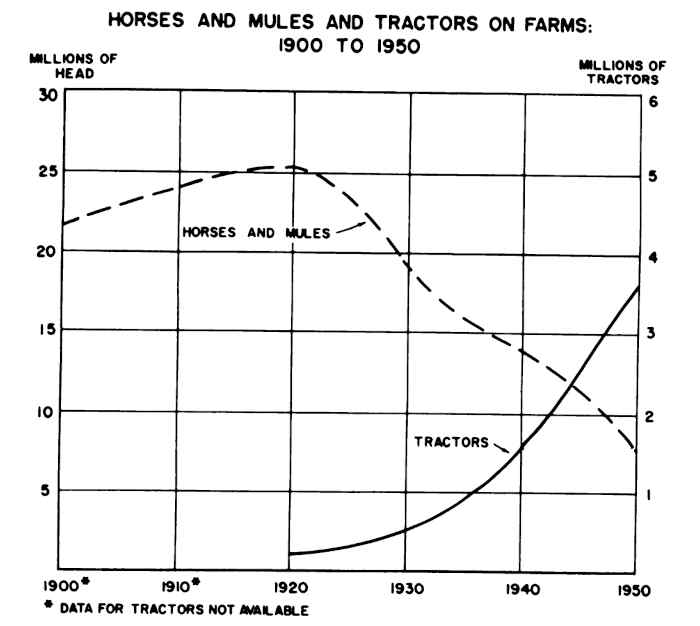

Or consider the internal combustion engine, an innovation conventionally discussed in relation to vehicular transport, but of immense importance to global agriculture. In early twentieth century US farms, the small gasoline engine (the ‘Otto’ engine, a German innovation), between three-fourths and ten horsepower, was an important source of stationary power for threshing grain, pumping water, sawing wood, baling hay, shelling corn, separating cream, and grinding feed, most of these traditionally performed by women and children. The stationary gasoline engine could run safely unattended, was more predictable than wind-power, more economical for small jobs and required less skilled supervision, offering a more reliable and less-resource intensive alternative to the tread and sweep power generated by horses for small tasks. It was estimated that 2.5 million stationary gas engines were in use in 1924 in US farms, concentrated in the North. But the combustion engine was still no match for the horse and mule, which remained the most significant single source of power on US farms until mid-century.

Working power on farms. Graph showing the trend of the number of horses and mules (in millions of head) and tractors (in millions) on US farms from 1900 to 1950. Note the dominance of horses and mules until the 1940s. Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, United States Census of Agriculture: 1950 Vol. V, Special Reports, Part 6, Agriculture 1950 – A Graphic Summary (Washington D.C., 1952). https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/United_States_Census_of_Agriculture_1950/LEwOm9d1nokC

Gasoline-powered tractors (particularly the Fordson) came into use in Midwestern wheat and corn fields in this period, but it was not until after the Second World War and with the introduction of general-purpose tractors and auxiliary improvements that it was rapidly adopted, even in the South, for row crops such as cotton and tobacco. By 1960, there were 4.5 million gas tractors in use in US farms, while the number of horses and mules fell below 8 million, against 22 million in 1900. However, this was far from a simple story of displacement, as farms often relied on both sources of traction power for different purposes, even as the trend was towards increasing tractorisation.

In Asia, it was the diesel engine, in small and large varieties, that was widely used in farms. While accounts of the Green Revolution have underscored high yielding variety (HYV) seeds, the region of the Punjab and United Provinces in India typically associated with this phenomenon in fact saw productivity increases as a result of the adoption of fertilisers and deep tubewells after the 1960s, supported by state rural electrification schemes and subsidies. However, as far as South Asia goes, it is not the electrified deep tubewell that is typical, but the smaller shallow tubewell and small low-lift pump powered by single-cylinder diesel engines. In Bangladesh, by 2006, there were about 1.2 million shallow tubewells powered by Chinese diesel engines, against 24,506 deep ones.

A diesel-powered shallow tubewell irrigates rice seedlings in Jamalpur, northern Bangladesh. Mamunur Rashid / Alamy.

We see a similar trend in shallow tubewell irrigation in Sri Lanka, Nepal, Thailand, and India, beyond the GR regions. Smaller diesel-powered two-wheel tractors similarly underpin Chinese agriculture, numbering some 17 million in 2012, followed by Thailand with 1.8 million units, but diesel engines were used for a wide variety of purposes in these regions. Interestingly, by the late 1990s the world leader in the production and use of large four-wheel diesel tractors was India, increasing from 100,000 in 1970 to 2.6 million in 2000, typically used in large wheat and rice farms in Punjab, while the number of draught animals in use declined from 82.6 million to 60.3 million, still a significant number, and of particular importance to smaller farmers. India today is the largest producer and market for 4WT tractors in the world.

India es el mayor fabricante mundial de tractores con el 50% de la producción mundial en 2016. También constituye el mercado de tractores más grande del mundo. Wikimedia.

We know far too little of the conditions of the regional adoption of these innovations, the role of firms and state institutions in these developments, and their impact on existing techniques, farm sizes, cropping patterns, and indeed on rural societies and rural politics. But a clear-eyed assessment of this empirical reality, without the blinkers of our dominant models, is a necessary first step.

Shankar Nair

Department of History, King’s College London

How to cite this paper:

Nair, Shankar. Agricultural techniques in the twentieth century. Sabers en acció, 2025-06-04. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/agricultural-techniques-in-the-twentieth-century/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Recommended reading

Angela Lakwete, Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003).

David Edgerton, The Shock of the Old: Technology and Global History since 1900, Reprint edition (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Eric R. Wolf, Europe and the People Without History (University of California Press, 1982).

Nick Cullather, The Hungry World America’s Cold War Battle Against Poverty in Asia (Harvard University Press, 2010).

Sidney W. Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (NY Penguin, 1985).

Ulbe Bosma, The World of Sugar: How the Sweet Stuff Transformed Our Politics, Health, and Environment over 2,000 Years (Harvard University Press, 2023).

Studies

Alan L. Olmstead and Paul W. Rhode, ‘Reshaping the Landscape: The Impact and Diffusion of the Tractor in American Agriculture, 1910-1960’, The Journal of Economic History, 61 (2001), 663–98.

Ariel Ron, ‘When Hay Was King: Energy History and Economic Nationalism in the Nineteenth-Century United States’, The American Historical Review, 128 (2023), 177–213.

Carrie A. Meyer, ‘The Farm Debut of the Gasoline Engine’, Agricultural History, 87 (2013), 287–313.

Deborah Fitzgerald, Every Farm a Factory: The Industrial Ideal in American Agriculture (Yale University Press, 2010).

G. Singh, ‘Agricultural Mechanisation Development in India’, Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 70 (2015), 64–82.

Govindan Parayil, ‘The Green Revolution in India: A Case Study of Technological Change’, Technology & Culture, 33 (1992), 737-756.

Kapil Subramanian, ‘Revisiting the Green Revolution: Irrigation and Food Production in Twentieth Century India’, unpublished PhD thesis (King’s College London, 2015).

Marci Baranski, The Globalization of Wheat: A Critical History of the Green Revolution (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022).

Nick Cullather, ‘The Foreign Policy of the Calorie’, The American Historical Review, 112 (2007), 337-364.

Patrick Joyce, Remembering Peasants: A Personal History of a Vanished World (Random House, 2024).

Paul Brassley, David Harvey, Matt Lobley and Michael Winter, The Real Agricultural Revolution: The Transformation of English Farming, 1939-1985 (Boydell & Brewer, 2021).

Prakash Kumar, Timothy Lorek, Tore C. Olsson, Nicole Sackley, Sigrid Schmalzer, y Gabriela Soto Laveaga, ‘Roundtable: New Narratives of the Green Revolution’. Agricultural History, 91 (2017), 397-422.

Shankar Nair, ‘Technology and Industry in a Colonial Economy: Steam Cotton Ginning and Leaf-Cigarette Manufacture in Late Colonial India, 1860-1940’, unpublished PhD thesis (King’s College London, 2024).

Stephen Biggs and Scott Justice, ‘Rural and Agricultural Mechanization: A History of the Spread of Small Engines in Selected Asian Countries’, May 26, 2015. IFPRI Discussion Paper 1443 (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2623612).

Sources

U.S. Bureau of the Census, United States Census of Agriculture: 1950 Vol. V, Special Reports, Part 6, Agriculture 1950 – A Graphic Summary (Washington D.C., 1952). https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/United_States_Census_of_Agriculture_1950/LEwOm9d1nokC

Websites and other sources

Angela Lakwete, ‘Fones McCarthy’, Encyclopaedia of Alabama, February 22, 2007. https://encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/fones-mccarthy/

Hannah Ritchie, ‘Yields vs. land use: how the Green Revolution enabled us to feed a growing population’, Our World in Data, 2007. https://ourworldindata.org/yields-vs-land-use-how-has-the-world-produced-enough-food-for-a-growing-population