—Women and commoners in the democratisation of science.—

Between 1797 and 1803, the daily press occasionally published news about the scientific events organised in the Coliseo de los Caños del Peral in Madrid, the Coliseo de Comedias in Valencia or the Teatro de Santa Creu in Barcelona by a certain “Francisco Bienvenido”, as the Frenchman François Bienvenu (1758-1831) was renamed in the Spanish media. For his visitors’ pleasure, instruction or the practical interest, Bienvenu combined several types of demonstrations: pneumatic phenomena, recently discovered and explained by new theories of chemistry, interesting practical applications of chemistry to the analysis of water and wine, and an endless number of spectacular electrical and magnetic phenomena. As if that were not enough, he also included phantasmagoria, produced with magic lanterns and catoptric machines, and experiments on living and dead animals, in which they were subjected to electric shocks or to the action of new gases. One can easily imagine the audience’s surprise at these scientific shows. In addition to these functions, those interested were invited to enrol on shorter courses, taught at his private residence, with schedules and content adapted to the attendees. Furthermore, for those who wanted to recreate such experiments in their homes or look into these issues on their own and at their own risk, Bienvenu made a wide range of versions of his instruments available, built by himself and sold at an affordable price to the most well-off people in his audience. He also offered to act as an intermediary for the importation from Paris of other models advertised in his catalogue. After-sale care was also guaranteed. Bienvenu made himself available for the repair and improvement of damaged or outdated instruments that its customers wanted to update.

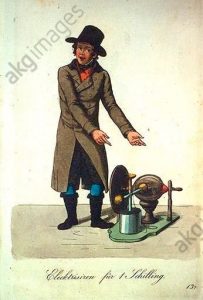

Travelling demonstrator offering to “electrify for a shilling” in Hamburg, late 1755 (drawing by Cornelius Suhr, ca. 1808). Akg images.

The success of his shows, courses and business must have been great, if we consider the impact they had in the daily press. It is possible to find more than half a thousand news articles on his visit to the Iberian Peninsula, where he worked in Cadiz, Seville, Barcelona, Valencia and Madrid. Press reports testify to the large turnout at his courses, which forced him to open double sessions every day. They were attended by doctors, pharmacists, artisans, farmers, nobles, artisans, clerics and, also, women. Bienvenu offered entertainment for the less educated and learning for the initiated, with a varied and flexible programme of lessons and demonstrations that combined instruction, fun and usefulness.

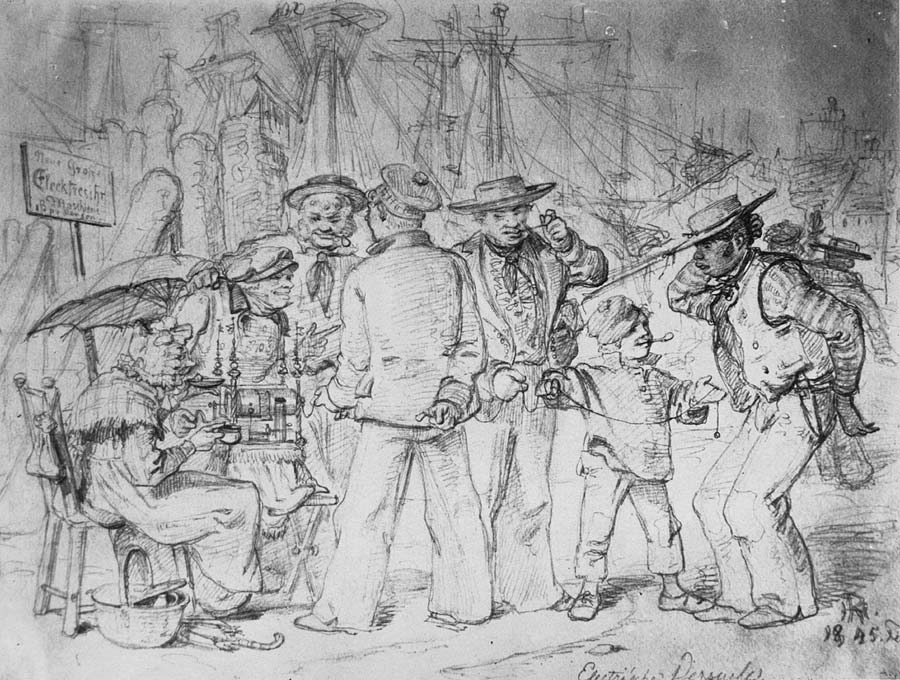

Bienvenu was far from a unique case. Hundreds of demonstrators like him toured theatres, squares and halls in Europe offering public sessions where the most recent experiments and scientific theories became popular shows. Instruction, delight, or interest in their practical application attracted people of very diverse classes and conditions. For these itinerant demonstrators, science had become a way of life, almost in the same way as it was for more renowned authors who organised public courses in physics, chemistry and other sciences in prestigious academic institutions. Bienvenu himself had acquired his training through these types of public courses in Paris, as well as by reading the memoirs published in specialist publications or in the daily press. He thus learned to build and manage the instruments shown in the courses or described in the publications, using the numerous public and private laboratories found in large cities.

Electricity demonstrations in a German harbour, based on a design by Henry Ritter (1816-1853), early 19th century. Old Master Drawings.

The vast majority of these street demonstrators made no relevant contributions to science, which condemned them to oblivion. However, their work was very important from a pedagogical point of view: they adapted instruments and experiments for use in lessons and demonstrations and devised ways to make research results available to the general public. Their courses and demonstrations were also essential to ensure that sciences such as physics and chemistry gained wide social recognition and became ‘public sciences’. The unquestionable democratisation that the cultivation of the sciences achieved during the Enlightenment did not mean that access was equal, nor even that it was open to all, and especially to all women. Among the people excluded from this new intellectual, professional and economic undertaking were women, who were limited to the role of spectators in courses and demonstrations, or as readers of the flourishing scientific literature written for them during the eighteenth century by men of science concerned with the education of women and also interested in the rich publishing market that this sector of the public represented. However, the cracks opening in this intellectual gender segregation were many and some were of great significance. Marie-Anne-Pierrette Paulze (1758-1836) was the leading figure in one of them.

Pen and ink drawing of Antoine Lavoisier performing a breathing experiment while his wife takes notes. Attributed to Marie-Anne-Pierrette Lavoisier (ca. 1790). Wellcome Collection.

The painter Louis David immortalised Antoine Lavoisier along with his wife in a scene which has become an icon for the revolution in chemistry. Madame Lavoisier appears here as the muse inspiring her husband in the writing of his revolutionary memoirs, surrounded by the most representative instruments of the new chemistry. This image contrasts with the one offered by the drawings made herself, where she appears integrated in the work of the laboratory, taking notes of the results of the experiments on breathing. The image Marie-Anne Paulze wanted to convey of herself in these drawings is much closer to what her work really meant for the origin, circulation and acceptance of the ideas attributed to her husband.

Portrait of Antoine Lavoisier and his wife, by Jacque Louis David (1788). Metropolitan Museum (New York).

The accounts of science of this period have highlighted her work as a translator and manager of her husband’s international scientific correspondence, thanks to her mastery of several languages. They also underline her knowledge of drawing and painting, acquired with her teacher and creator of the couple’s famous portrait, Louis Jaques David. To her, we owe the prints of instruments, which illustrate the treatise on elementary chemistry by her husband, Antoine Lavoisier. Her important work in the persuasive campaign carried out by Lavoisier and his collaborators to spread their ideas on the composition of matter and the nature of chemical reactions. The meetings and gatherings organised by Marie-Anne Paulze in the couple’s private residence, were attended by guests of the stature of Volta or Priestley, and countless travellers were able to get to know the new experiments and interpretations that Lavoisier and his collaborators defended in academic forums first-hand.

The recognition of her activity as a collaborator in the works of her husband has, however, eclipsed her own creative work. Making the prints from the annotations and diagrams of the work implied technical knowledge of the instruments and their operation that went beyond mere artistic skills. In the same way, translating of texts on chemistry, writing letters in reply to the dozens of correspondents, recording experimental data and participating in the meetings involved much more than the mastery of writing and good manners. Madame Lavoisier, the muse and assistant to her husband, has long eclipsed Marie Anne Paulze, a translator, instrument designer and polemicist. One should ask whether this recognition as a collaborator does not also overshadow her activity as an experimenter and theorist of chemistry, which is much more important than what the social norms of her time allowed her to show and what later historians of science have known how, or wanted, to see.

Antonio García Belmar

IILP-UA

How to cite this paper:

García Belmar, Antonio. Enlightened lives. Sabers en acció, 2020-12-24. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/enlightened-lives/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Recommended reading

Fara, Patricia. Pandora’s Breeches: Women, Science and Power in the Enlightenment. London: Pimlico; 2004.

Sutton, George. Science for a Polite Society. Gender, Culture and the Demonstration of Enlightenment. Boulder: Westview Press; 1995.

Golinski, J. Science as Public Culture: Chemistry and Enlightenment in Britain, 1760-1820, Cambridge, University Press; 1992.

Studies

Antonelli, Francesca. ‘Becoming Visible. Marie-Anne Paulze-Lavoisier and the Campaign for the “New Chemistry” (1770s-1790s)’. Ambix, 2022; 69 (3): 221–42.

Harding, Sandra, Sciences from Below: Feminisms, Postcolonialities and Modernities, Durham (USA) and London, Duke University Press, 2008.

Kawashima K. The Evolution of the Gender Question in the Study of Madame Lavoisier. HistoriaScientiarum, 2013; 23(1): 24-37.

Mazzotti, Massimo ‘Newton for Ladies: Gentility, Gender and Radical Culture’, British Journal for the History of Science, 2004; 37(33): 119–146.

Neelam Kumar (ed.) Gender and Science: Studies across Cultures, New Delhi: Cambridge University Press India, 2012.

Rossiter, Margaret W. “The Matthew/Matilda Effect in Science”, Social Studies of Science. 1993; 23(2) 325–341.

Serrano, E. “Chemistry in the city: the scientific role of female societies in late eighteenth-century Madrid”. Ambix. 2013; 60(2): 139-159.

Suay-Matallana Ignacio, Bertomeu-Sánchez, José Ramón, François Bienvenue y la popularización científica en la Ilustración demostraciones experimentales, entretenimiento y públicos de la ciencia, Enseñanza de las ciencias, 2016; 34 (2): 167-184

Schiebinger, Londa, The Mind Has No Sex? Women in the Origins of Modern Science, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Poirier, Jean-Pierre. La science et l’amour: Madame Lavoisier. Paris, Pygmalion; 2004.

Watts, Ruth. Women in Science: A Social and Cultural History. London: Routledge, 2007.

Sources

Diario de Madrid, 19 July 1797, page 1. Available here.