—Nerves, gender and modernity at the end of the 19th century.—

In 1869, the New York neurologist George Miller Beard (1839–1883) described a new disease before the American Medical Association: neurasthenia, or nervous exhaustion, which in it’s Greek etymology meant “lack of nervous strength.” This condition was considered a result of excessive intellectual work and mainly affected people dedicated to liberal professions, such as lawyers, bankers and doctors. It was characterized by weakness and physical and mental exhaustion, which manifested itself in symptoms such as insomnia, headaches, digestive and sexual disorders, obsessive ideas, phobias and the inability to focus attention and make decisions.

Beard acknowledged that the disease had always existed, but noted that its incidence had increased significantly in the years before his 1869 talk. This increase was no coincidence. Beard explained in his works A medical treatise on nervous exhaustion (neurasthenia) (1880) and American Nervousness: its causes and consequences (1881), neurasthenia was the result of modern civilization, characterised by (a) the new communication technologies that allowed the rapid exchange of news and messages; (b) steam engines, which connected different parts of the country through railway systems; (c) the development of sciences; and (d) the education of women, which allowed them to leave the private and domestic sphere and occupy public space, symbolizing social advances. For Beard, these features of modern civilization were especially found in the United States, where cases of neurasthenia far exceeded those in other nations.

The association between neurasthenia and modern civilization gave the disease great cultural significance. Garnering the moniker ‘the disease of the century’, it became a true marker of modern US American life. At that time, the country was experiencing unprecedented economic and industrial growth in a time called “the Gilded Age.” Large cities like New York, with their skyscrapers, trams, department stores and electrification, were the symbol of this growth. In large cities, new professions such as stock market speculators emerged, salaries increased and migration from rural areas proliferated. Everything seemed possible.

Neurasthenia – a disease that mainly affected the bourgeois and urban class – appeared in this context of progress, achieved thanks to intellectual work. Getting sick was not desirable, but the disease acted as yet another marker of the (apparently unstoppable) new American civilization. The diagnosis served, therefore, as both a signal of virtue and a way to naturalize the social hierarchy that placed the bourgeois and urban man at the top as the person most responsible for the progress of society.

New York’s Newspaper Row had the tallest skyscrapers in the city, built in the late 19th century. 1906, Wikimedia.

To explain the mechanisms of the disease, Beard used metaphors of modernity, comparing the human body to a bank account or an electric battery. Throughout the day, energy – represented by money or electricity – was spent on various tasks. Neurasthenia appeared when energy had been overspent and a deficit occurred: the bank account went into negative numbers, or the battery ran out of charge. The metaphors not only served to illustrate the effects of pathology, but also to conceive both the disease and the human body in the economic and technological terms characteristic of modernity.

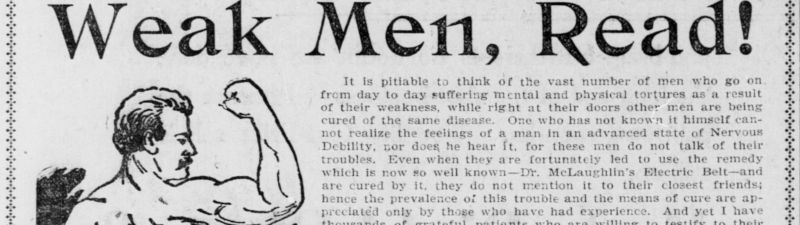

This general approach was also reflected in the suggested treatments for neurasthenia. Physicians recommended diets, rest, and trips out of the city in order to disconnect from the over-stimulation that they carried out on the nervous system. Spas became a typical destination for neurasthenics seeking a break from their busy lives, as well as traveling around Europe. For those who did not have so many financial resources, tonics to invigorate the nervous system and books dedicated to giving advice proliferated, such as the work Wear and Tear, or Hints for the Overworked (1871) by neurologist Silas Weir Mitchell. Electrotherapy – Beard’s specialty – was also a popular way to recharge the nervous system. The market offered a whole series of devices supposedly charged with electricity, from belts to combs, which promised to strengthen the nervous system and restore health. In this way, the management of the disease also served to determine the ideals of health and masculinity: the good modern subject had to be able to manage his energy and develop a strong willpower to act against the threat of modernity, thus guaranteeing the country’s progress.

Advertisement for Dr. McLaughlin’s electric belt. The Arizona Republican: Sunday Morning, February 1, 1903, p. 6. The Library of Congress: Chronicling America online data base.

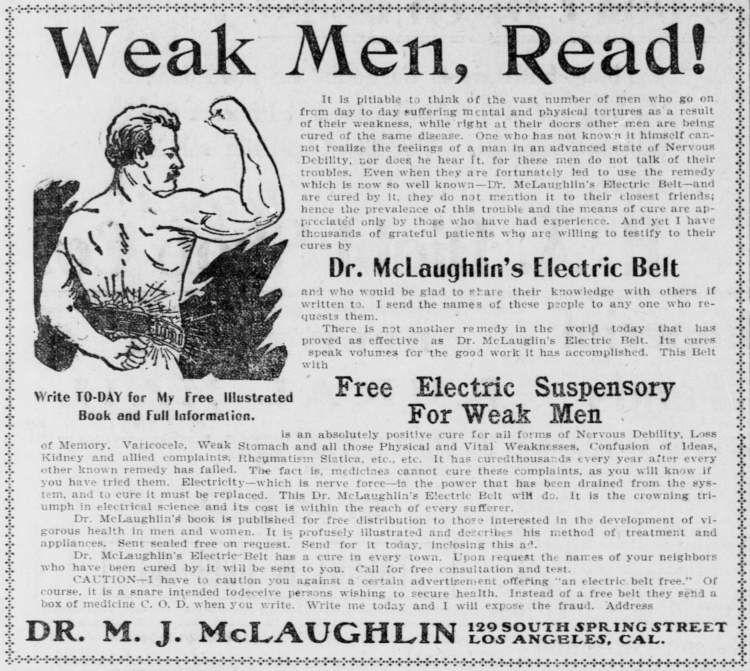

Neurasthenia therefore not only defined the parameters of health, but also of new ways of being modern. These parameters were established in significantly gendered terms. Its diagnosis and treatment among bourgeois white women in the US is a clear example of this. As we have seen, Beard claimed that one of the features of modern civilization was the rise of the educated and independent modern American woman. This ideal gained its maximum expression in the figure of the “Gibson Girl,” represented as a young single woman who enjoyed art, exercise, and dressed in the latest fashion. The Gibson Girl emerged as a critique of the figure of the Victorian bourgeois woman, restricted to the domestic space and inhibited in the expression of her personality and desires.

The Gibson Girl represented the ideals of the new modern woman: young, beautiful and emancipated, standing in stark contrast to the traditional values that characterised the Victorian woman. Charles Dana Gibson, The Crush (1901). Wikimedia.

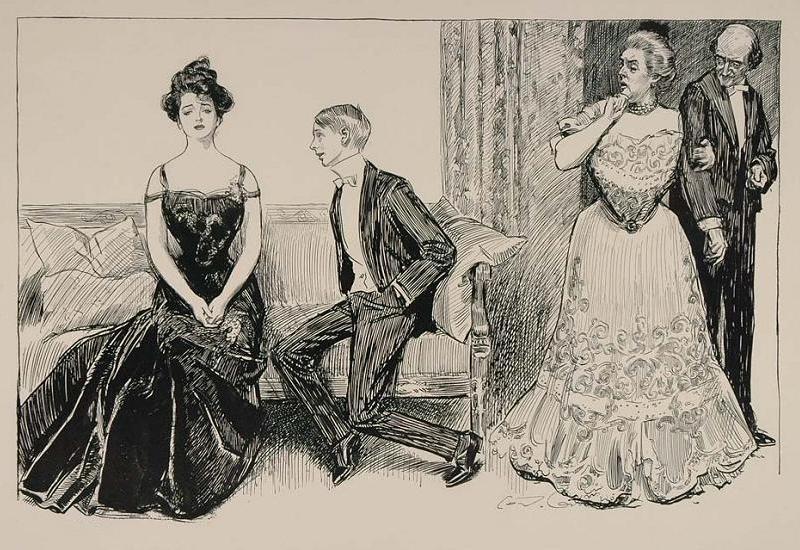

Upper-middle-class Victorian women typically suffered most from neurasthenia, to the point that Mitchell – the author of Wear and Tear – created an entire treatment system aimed at them to strengthen the nervous and circulatory system. The so-called “rest cure” consisted of limiting all types of physical and mental activity of the patient, who had to spend between six and eight weeks prostrate and isolated from her environment. All her functions were in charge of a doctor or a nurse who dedicated herself to her day and night, feeding her a special diet, bathing her and applying treatments such as electrotherapy and massages, all to strengthen the body’s functions from the outside, without her having to make any kind of effort. Over the course of the treatment, the patient slowly regained control of her body and gradually increased activity.

The rest cure consisted in the patient’s isolation, coupled with a regimen of diet, exercise, and massage. Laura Gilpin (1923), The Rest Cure. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Online collections.

Mitchell’s treatment had an important impact in the medical field, gaining popularity in other countries like England. For many women, the remedy helped them distance themselves from their domestic responsibilities for a time and escape the oppressive role that society imposed on them as a mother and housewife. However, for others, the treatment’s extreme infantilization of the patient led to a worsening of the neurasthenic symptoms, with some female patients ending up on the verge of being admitted to an asylum. Such was the experience of the suffragist writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman, who narrated her experience in a short story titled “The Yellow Wallpaper” and published in 1891 in the literary magazine The New England Magazine. After giving birth to her daughter, the author became ill with neurasthenia and turned to Mitchell to treat her condition. The results were disastrous: seclusion and the absolute limitation of writing and mental activity brought her to the brink of madness and she was only able to recover by breaking the restrictions imposed by the doctor and denouncing the treatment through her story.

The different responses to the rest cure, as well as the medical attitudes toward women’s intellectual activity, are indicative of the ambiguity that characterized neurasthenia. This was also reflected in the international reception towards the disease. Not everyone agreed with the idea that neurasthenia was a positive marker of advanced modernity, and even less so that the culmination of this was American civilization. The disease served to criticize the bourgeois lifestyle, characterized by excess and luxury, in a period in which social revolts of workers, immigration and poverty were the daily bread.

Cover of a 1901 edition. Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1901), The Yellow Wallpaper, Small, Maynard & Company. Wikimedia.

In this sense, the end of the 19th century was marked by a transnational discourse concerned with degeneration and the struggle between countries to present themselves as the most civilized. Each nation established its own markers of what civilization consisted of, using them as a way of praising national qualities and condemning foreign ones. Doctors from countries such as Spain and France argued that neurasthenia was a sign of the excessive ambition that characterized US American society. Treatments such as the rest cure served as another example of the savage practices carried out in the US and rejected in truly civilized countries. In these contexts, the supposed low incidence of neurasthenia served, therefore, as a way of demonstrating that these countries did not suffer from bad modernity, but that one could still enjoy a full life, despite not having the necessary economic and industrial advances of the USA.

However, despite these criticisms, neurasthenia became popular in many countries at the turn of the 20th century. The diagnosis and its treatments operated as a key element in the discourses and practices around modern life and acted as a bridge between traditional values and the changes that were coming in contexts as varied as Spain, Russia and Japan. Associated with progress and the social roles of bourgeois men and women, it served to establish the parameters between health and illness, as well as social roles and national identity far beyond the United States. The so-called disease of the century was, above all, a response to the threat and promise of modernity, and a way of generating new identities in the face of a world characterized by both uncertainty and possibility.

Violeta Ruiz Cuenca

IMF-CSIC

How to cite this paper:

Ruiz Cuenca, Violeta. Neurasthenia: the disease of the century. Sabers en acció, 2024-05-08. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/neurasthenia-the-disease-of-the-century/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Recommended reading

Ruiz, Violeta. Neurasthenia, Civilisation and the Crisis of Spanish Manhood, c. 1890–1914. Theatrum historiae. 2020, 27: 95-119.

Studies

Beliaeva, Anastasia. Creating the New Soviet Man: The Case of Neurasthenia. Social History of Medicine. 2022; 35 (3): 927-945.

Gijswijt-Hofstra, Marijke, and Roy Porter, eds. Cultures of neurasthenia from Beard to the First World War. Amsterdam: Rodopi; 2001.

Lutz, Tom. American Nervousness, 1903: An Anecdotal History. Ithaca, Cornell University Press; 1991.

Mansell, James G., and Daniel Morat. Neurasthenia, Civilization, and the Sounds of Modern Life. In Morat, Daniel, ed. Sounds of Modern History: Auditory Cultures in 19th-and 20th-Century Europe. New York: Berghan; 2017, pp. 278-304.

Smith-Rosenberg, Carroll. Disorderly conduct: Visions of gender in Victorian America. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1986.

Williams, Katherine Elmire (ed). Women on the Verge: The Culture of Neurasthenia in Nineteenth Century America. Stanford, CA: Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University; 2004

Wu, Yu-Chuan. A disorder of qi: Breathing exercise as a cure for neurasthenia in Japan, 1900–1945. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 2016, 71 (3): 322-344.

Sources

Beard, George Miller. A medical treatise on nervous exhaustion (neurasthenia). New York: Putnam; 1880.

Beard, George Miller. American nervousness, its causes and consequences: a supplement to nervous exhaustion (neurasthenia). New York: Putnam; 1881.

Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. The Yellow Wallpaper, in The Yellow Wallpaper and Selected Writings. London: Virago; 2014 [1890]: p. 3-23.

Mitchell, Silas Weir. Wear and tear: Or hints for the overworked. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1899.

Mitchell, Silas Weir. Fat and blood: an essay on the treatment of certain forms of neurasthenia and hysteria. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1902.

Ribas Perdigó, Manuel. El tratamiento de la neuro-astenia. Barcelona: Imprenta de Amat y Martinez; 1892.

Proust, Albert; Ballet, Gilbert. L’hygiène du neurasthénique. Paris: Masson et Cie, éditeurs; 1897.

Websites and other sources

Schnittiker, Jason. After many false starts, this might be the true age of anxiety. Psyche. 16 November 2021. https://psyche.co/ideas/after-many-false-starts-this-might-be-the-true-age-of-anxiety

Shaffner, Anna Katharina. Why exhaustion is not unique to our overstimulated age. Aeon. 6 July 2016. https://aeon.co/ideas/why-exhaustion-is-not-unique-to-our-overstimulated-age