—The naturalization of synthetic vanillin from 1874 until 1959.—

Is it possible to describe a particular flavor as the taste of a century? The variety of culinary landscapes suggests that it might be difficult to claim such a dominance for only one component. But in the case of vanillin, the characterization as a taste of a century seems to be adequate. Since the late 19th century, the production and selling of vanillin grew significantly. While the industrial production of synthetic vanillin started with yearly 25kg, the quantity in the late 1930s was more than 300.000kg. According to the German Association of Flavor Manufacturers (Deutscher Verband der Aromenindustrie e. V. (DVAI)), the demand for vanillin in the 21st century is more than 15.000t. It is used amongst others in food, drinks, and cosmetic products. Vanillin is quasi omnipresent in our daily lives and without consciously knowing it, most of us are imprinted on the sweet vanilla flavor.

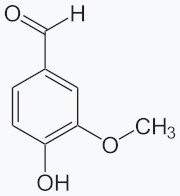

Chemical structure of vanillin. Wikipedia.

How did vanillin become such a dominant flavor and fragrant? In the following the integration and naturalization process of synthetic vanillin will be examined based on industrial developments and marketing strategies in Germany in the first half of the 20th century. First, the origins of industrial synthetic vanillin production will be presented. Who produced this flavoring substance? Who influenced the market? Afterwards, two examples of marketing and naturalization strategies will be given. How was synthetic vanillin perceived? Where was it used and what were the suggested advantages compared to vanilla-beans? What did the industry do to convince people to consume their vanillin products? Third, the cultural and social status of vanillin will be studied through the lens of flavor regulation in the late 1950s. What impact did the early naturalization of synthetic vanillin have on its juridical handling? What does its standing tells us about the social and economic value of this flavor? Answering these questions makes clear why vanillin may fairly be called the taste of a century.

The production of synthetic vanillin on an industrial scale started in 1874 with the foundation of Haarmann’s Vanillinfabrik, later called Haarmann & Reimer and today known as Symrise. The chemists and entrepreneurs Wilhelm Haarmann and Ferdinand Tiemann succeeded in synthesizing this flavoring substance out of coniferin. Based on that discovery they started a small manufacture in Holzminden, Lower Saxony. Improving the production methods and finding new raw materials, the synthesis of vanillin became easier, more efficient, and cheaper over time.

Vanilla beans. Wikipedia.

Haarmann & Reimer concentrated its production on the synthesis based on Eugenol, a component of the essential oil of cloves. Another possible starting point was found in Guajacol, a well-known compound in the general chemical industry. In the 1920s and 1930s, several companies from the chemical and pharmaceutical industry entered the lucrative vanillin market. Powerful and famous firms like Rhône-Poulenc (France), Monsanto (USA/UK), Hoffmann-la-Roche (Switzerland), C. F. Boehringer & Soehne and Agfa (both Germany) started their own vanillin production and began to dominate the national and international vanillin trade. Vanillin was not only a matter of specialists for flavors and fragrances but entered the portfolio of powerful generalists of the chemical industry.

In the beginning of the 20th century, Haarmann & Reimer wanted to introduce their synthetic vanillin to a broader public. In cooperation with the social activist Lina Morgenstern, they published a small recipe collection for general households. Beside the recipes there was a short foreword written by Morgenstern introducing the flavoring agent and explaining its origins. She first gave an explanation about the botanical character of the vanilla plant and its habitat outside of Europe. Afterwards she praised the German chemistry for having been able to introduce the excellent taste of vanilla in Germany as well. Using a quote from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, she poetically embedded the synthesis of vanillin and presented its production and its qualities in a more than positive manner. Morgenstern described the easy handling, the fine taste, and the purity of synthetic vanillin in contrast to the more difficult usage of vanilla beans. According to her description, the synthetic product was as good as the natural one if not better. Considering the cover of the recipe collection, where the name of the company Haarmann & Reimer is prominently printed on the front as part of the title and where their patent seal for vanillin is on the back, and reflecting the praise of Tiemann and Haarmann, the chemical industrial origin of the flavoring agent was not at all hidden. On the contrary, this fact was put to the forefront and had an entirely positive connotation. Because of the chemical synthesis the taste of vanillin was available in Germany for a broader public. These arguments can equally be found in a recipe collection from the German food company Dr. Oetker.

Lina Morgenstern recipe collection cover. Paulina S.Gennermann (2023), Eine Geschichte mit Geschmack…. De Gruyter Oldenbourg, p.35.

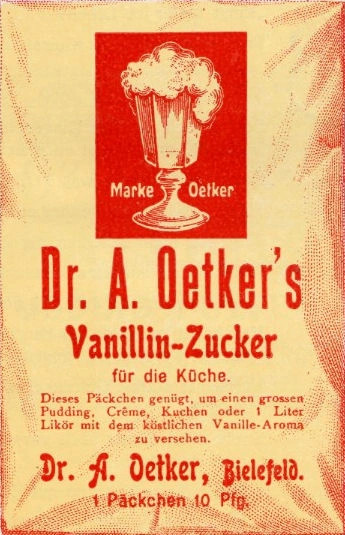

Morgenstern’s recipe collection and that of Dr. Oekter have important aspects in common regarding the presentation of vanillin. Both present this particular flavoring agent as the only component forming the vanilla flavor. While it is true that vanillin is the key component of vanilla flavor, the taste of vanilla beans is more complex than this. Nevertheless, the recipe collections implicated that vanillin is the entire vanilla flavor. This impression was strengthened by the usage of the terms “vanilla“ and “vanillin“. All recipes only contained synthetic vanillin, in the case of Dr. Oetker their vanillin sugar, but no vanilla beans. Yet, the recipe titles spoke of “vanilla“, for example “Vanilla biscuits” or “Vanilla cake”. The combination of the argumentation about the origin of vanilla taste and the usage of language supported the naturalization of synthetic vanillin and its synonymization for vanilla. Vanillin quasi became vanilla.

Vanillin sugar (Vanillin-Zucker), 1894, Dr. Oetker. Dr. Oetker.

In the first German Essence Decree (“Essenzen-Verordnung”) from 1959, the success of industrial naturalization strategies became visible. This Decree followed the 1958 renewed Food Law and included for the first time non-natural flavorings in its guidelines. The instructions for the declaration of flavoring substances provide an interesting insight into the social, cultural, economic and then juridical status of synthetic vanillin. In general, non-natural (in this decree called “artificial”) flavors had to be declared as such and every description suggesting naturalness were prohibited. But in paragraph 5, part 2 the German Essence Decree stated that the use of vanillin in a food product or a flavor mixture did not hinder the declaration ‘natural’ as long as vanillin was not used as the primary gustatory element. Being only a subordinated component and not the dominant flavor, synthetic vanillin could be used without being declared as ‘artificial’. At first this might not seem such a big deal considering the only negligible influence on the overall taste in those cases, but at a second glace it tells us a lot about the cultural value of synthetic vanillin, its naturalization, and explains its continuous success story until the 21st century.

During the first half of the 20th century, synthetic vanillin became widespread in common food products such as sweet pudding, cookies, and vanillin sugar. Throughout the decades, consumers got used to its taste, smell, and handling and synthetic vanillin became a mundane ingredient. Its presence in the kitchen was considered normal and direct concerns or public critiques were rare. The integration of this synthetic flavor into the general kitchen was strongly supported by the flavor and fragrance as well as the food industry, presenting and promoting synthetic vanillin as a natural or better than natural flavor of excellent taste.

The transformation of synthetic vanillin to a natural food ingredient found its juridical implementation in the German Flavor Decree of 1959 which demonstrates in an exceptional way how deep the naturalization of synthetic vanillin was already implanted in German society. Besides, the juridical exception for vanillin underlines the high amount used in food industry at that time. As widespread as vanillin was, it is possible that a lot of flavoring mixtures or food products might otherwise had to be declared as ‘artificial’. In short, the German Flavor Decree highlights two aspects: First, the successful naturalization of synthetic vanillin in the mid-20th century and second, the strong economic interest in this flavoring agent, its continuous naturalization, and its regular consumption.

Pudding with vanilla flavor, 1894, Dr. Oetker. Dr. Oetker.

Is it possible to describe a particular flavor as the taste of a century? Thinking about the long-going naturalization of synthetic vanillin and its enormous success, it seems adequate to call vanillin a taste of a century if not of centuries. Until today, the taste of vanilla, often represented by vanillin, attracts a lot of people from all over the world. Studying the history of this naturalization process outlines the changeable and complex nature of chemical substances and their values and functions in societies. Vanillin was integrated into mundane consumption and perceived as a natural substance even if its origin often lied in chemical industry.

Paulina S. Gennermann

Heidelberg University / Institute for History and Ethics of Medicine

How to cite this paper:

Gennermann, Paulina S. The taste of a century. Sabers en acció, 2024-02-07. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/the-taste-of-a-century/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Recommended reading

Gennermann, Paulina S. Eine Geschichte mit Geschmack: die Natur Synthetischer Aromastoffe im 20. Jahrhundert am Beispiel Vanillin. Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg; 2023.

Studies

Berenstein, Nadia. “Designing Flavors for Mass Consumption.“ The Senses and Society. 2018; 13 (1): 19-40.

Berenstein, Nadia. “Making a Global Sensation: Vanilla Flavor, Synthetic Chemistry, and the Meanings of Purity.“ History of Science. 2016; 54 (4): 399-424.

Ecott, Tim. Vanilla: Travels in Search of the Ice Cream Orchid. New York: Grove Press; 2004.

Stanzl, Klaus. Die Entstehung der Riechstoffindustrie im 19. Jahrhundert. Stuttgart: Stanzl (Druck und Vertrieb: epubli); 2019.

Stoff, Heiko. Gift in der Nahrung: zur Genese der Verbraucherpolitik Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag; 2015.

Vaupel, Elisabeth. “Betört von Vanille. Seit 500 Jahren begehrt – und immer noch Forschungsthema.“ Kultur & Technik. 2002; 47-51.

Vaupel, Elisabeth. “Ersatz für die Naturvanille : Rezeption und rechtliche Behandlung der Aromastoffe Vanillin und Ethylvanillin in Deutschland (1874-2011).“ Ferrum: Nachrichten aus der Eisenbibliothek. Stiftung der Georg Fischer AG. 2017; 89: 44-55.

Vaupel, Elisabeth. “Hermann Staudinger und der Kunstpfeffer.“ Chemie in unserer Zeit. 2010; 44 (6): 396-412.

Zwanenberg, Patrick van; Erik Millstone. “Taste and Power: The Flavouring Industry and Flavour Additive Regulation.“ Science as Culture. 2015; 24 (2): 129-156.

Sources

Bundesminister des Innern; Bundesminister für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Forsten. “Verordnung über Essenzen und Grundstoffe (Essenzen-Verordnung).“ Bundesgesetzblatt. 1959; 25: 747-750.

Morgenstern, Lina. Kochrecepte mit Anwendung von Haarmann & Reimer‘s patent. Vanillin. ca. 1900; private collection.

Unternehmen Dr. Oetker. Rezeptbuch B. Unternehmensarchiv Dr. August Oetker KG (OeFa): S3 40; 1910.

Websites and other sources

DVAI. Woher kommt Vanillin und wie stellt man es her? https://aromenverband.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/fact_sheets_vanillin.pdf

Symrise Official Website https://www.symrise.com/de/

Flavor & Extract Manufacturers Association. https://www.femaflavor.org/