—The role of imitation in technical change in early 20th- century London, New Jersey and Bogotá.—

Chlorination is one of the most radical transformations in modern water treatment. Its history illuminates our understanding of urban sanitation and public health in the early 20th century, but it also serves to correct misapprehensions in the historiography of modern technology, as pointed out by David Edgerton in the entry about the global history of science and technology.

Throughout the case of water chlorination, I deal particularly with the issue of how similar or different technical change is between the Global North/West and the Global South/Non-West. While taking differences seriously, I also demonstrate how experts in Bogotá, Colombia, did not hesitate to imitate water treatment technologies from England and the United States. Physicians and engineers in Colombia, as autonomous agents, put a premium on solving practical matters of public health, such as preventing waterborne diseases, using available knowledge and low-cost techniques from industrialised countries. That logic, however, is not exclusive to countries like Colombia. Indeed, industrialised countries themselves followed the same logic when it came to improving their own water supply systems. Imitation is a feature of global technical change, not only in developing countries, and not exempt from controversy, as I will show.

Chlorination is the use of chlorine as a disinfecting agent to eliminate bacteria from drinking water. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, physicians and sanitary engineers only used chlorine on sewage or experimentally to treat water during outbreaks of typhoid fever, but not as a permanent measure. Experts and citizens alike distrusted chlorine due to the unpleasant odour and taste it added to water and safety concerns. After all, putting chemicals into the water was, for some, contrary to the idea that ‘pure water’ was better obtained by protecting watersheds than by treating an already polluted source.

The chlorination of drinking water was first experimentally tested in Middelkerke, Belgium (1902) and Lincoln, England (1905), but it was only adopted as a permanent water treatment technology in the United States in 1908. From there, it spread worldwide, radically changing water management and reducing mortality and morbidity on an impressive scale. By the 1930s, chlorination had become a standard water treatment in most places. Why was this technology adopted so quickly? The main factor that made the minds of decision-makers in places as different as London, New Jersey or Bogotá was the low cost of this technology in comparison to alternatives considered superior, such as ozone, which made it a good choice to cope with economic challenges.

Despite obvious differences (cultural, religious, and economic), industrialised and developing cities shared a set of challenges that made imitation in water treatment possible and desirable between the late 19th and early 20th centuries: rapid urbanisation connected to capitalist development, increasing outbreaks of typhoid fever, private utilities unable to produce safe drinking water, and doctors and sanitary engineers still adapting their practices to germ theory.

The results of experiments in water treatment were widely known through papers published in academic journals, commercial initiatives, or even diplomatic cables. As with any technical field, water treatment had plenty of alternatives and none of them was destined to triumph. Ozone, quicklime, ultraviolet light, a combination of storing and slow sand treatment, and even the good old-fashioned protection of the source were available. Despite many considerations, the catalyst that pushed the decision in favour of chlorination was economic across the board.

Dr. John Leal, pioneer of chlorination in Jersey City. Wikimedia.

Jersey City was the first city to use chlorine as a permanent water treatment in 1908. The adoption of this process was, however, controversial. Due to water quality problems (high bacterial count) and breaches of contract, the city’s authorities sued the Jersey City Water Supply (the private company in charge) in 1906. A year later, in May 1907, the company received a court order to build “sewers and sewage disposal works for various towns in the watershed” to avoid pollution entering the supply. John Leal, a physician who acted as consultant to the company, suggested that chlorination, which he knew from contemporary experiments in Germany, England and some of his own, could be a cheaper alternative. After petitioning the court for time to try alternatives to the sewage system, a tremendously expensive option, he designed a ‘sterilisation plant’ in collaboration with a team of engineers and put it into function in September 1908, where he tried chlorine and other chemicals, including ozone, rejected on the same grounds as elsewhere: expensive and difficult to produce.

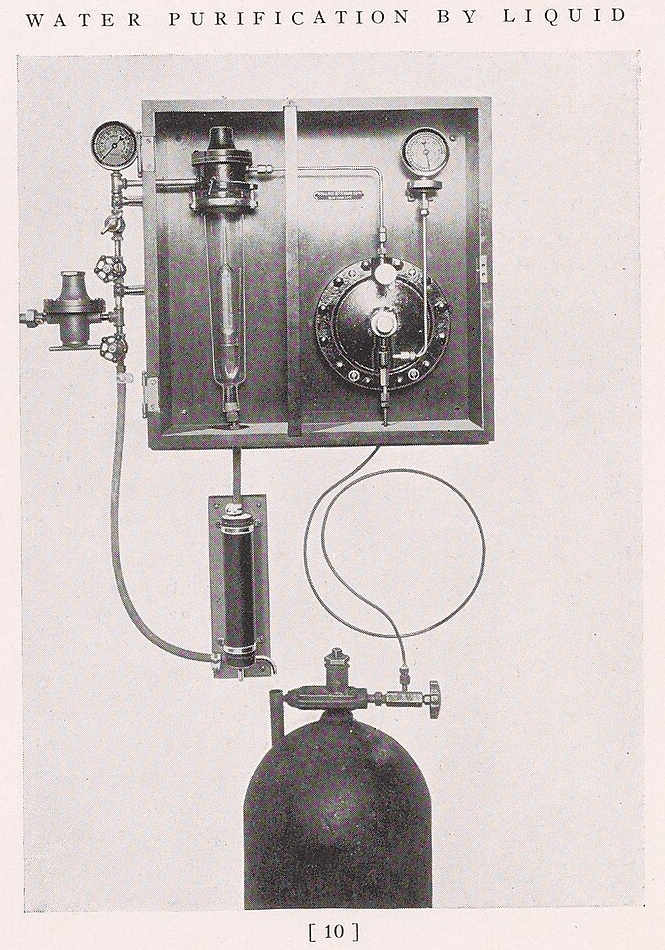

Dr. Leal initially reported to the court what he was doing as the ‘works,’ and only in 1909, the city came to know he had been chlorinating the water supply. The subsequent legal process was heated, with many experts in favour and against chlorine debating their arguments in court. The main difference of opinion was the choice between treating already polluted water, as chlorination did, or preventing water pollution, as sewage systems would do. After intense deliberations, though, the court approved the permanent use of chlorine on November 15th, 1910, arguing it was safe, effective as a bactericide, and low-cost. Following a rapid expansion in American cities, industrial improvements and scale production by companies like Wallace &Tiernan made liquid chlorine (compressed and cooled chlorine gas), the most popular version, as it was cheaper, and easier to transport and apply to the water supply, facilitating its global expansion.

Chlorinator in Wallace & Tiernan’s manual, Water Purification by Liquid Chlorine for Small Communities, 1915. Wikimedia.

At the beginning of the 20th century, London was a leading city in water treatment. The Metropolitan Water Board, under the direction of physician Alexander Houston (after the municipalisation of private utilities), used effectively a combination of storing in large reservoirs and slow sand filtration to provide safe drinking water to Londoners. Houston had conducted a large-scale chlorination experiment in Lincoln, England, in 1905 to deal with a typhoid outbreak and knew of experiments elsewhere. He was reluctant to chlorinate the river Thames water and, prior to 1916, to use chemicals as permanent water treatments. For him, chemicals were only appropriate as experimental or temporary treatments. Adding to the displeasure that citizens expressed at the odour and taste of chlorinated water, Houston believed, like other specialists, that ozone was the only bactericide ‘absolutely free from any source of reasonable objection.’

Sir Alexander Houston, director of Water Examination at London’s Metropolitan Water Board between 1905 and 1939. Wikimedia.

Ozone was expensive and difficult to produce. It hardly expanded beyond France, although it was admired everywhere. It was only when facing rising costs in his storage system during the Great War that Houston changed his mind about chlorine. The storage system, essential to Houston’s treatment, worked by pumping raw River Thames water to the Staines reservoirs using coal, whose cost became prohibitive during the war effort. When looking for alternatives, he was aware that cheap and humble chlorine had exceeded ‘the expectations even of the most ardent advocates of this method of treatment’ in the United States. Houston finally agreed to chlorinate London’s water supply in May 1916.

The chlorination of Bogotá’s water supply in 1920 followed years of intense controversy among doctors and sanitary engineers over the adequacy of chlorine. Bogotá began the 20th century in a dire drinking water situation: deficient infrastructure, legal disputes over ownership of the utility, and rampant waterborne diseases. Similarly to Jersey City, Bogotá’s authorities got into a legal dispute with the Compañía de Acueducto de Bogotá y Chapinero, a private utility, due to delays in coverage and water quality issues, which did not resolve until 1914 when the city was finally able to municipalise the water service. In the meantime, an ambitious plan presented by Pearson and Son, a global British engineering company, at the petition of Bogotá’s authorities in 1907, included adopting storing in large-scale reservoirs and slow sand filtration, as in London, but not chlorination. Ozone was also suggested but never adopted. Pearson’s plan, cherished by local doctors, was too expensive for the city’s meagre finances and could never be implemented. Bogotá depended on international credit to purchase the private company and improve its water infrastructure, and given the reluctance of the London banks, the main lenders of the city, both technical upgrading and municipalisation were delayed.

In this context of budgetary paucity, Bogotá’s authorities learned about chlorination. On May 8, 1917, a diplomatic cable from Eduardo Restrepo Sáenz, Colombia’s ambassador to Perú, reported on the success of ‘liquid chlorine’ in Lima. The same year, Roberto de Mendoza, an engineer, learned about the use of ‘liquid chlorine’ in New York and asked councilman Simón Araujo to endorse its use. Araujo responded positively, as he already knew about chlorination through William Gorgas, a doctor from the Rockefeller Foundation who was then visiting Colombia.

Old building of the Compañía de Acueducto de Bogotá y Chapinero. Wikimedia.

Mendoza began a public campaign in anonymous opinion columns, arguing that chlorine was effective and so much cheaper than Pearson’s plan. Bogotá’s Council attempted to purchase chlorinators from Wallace & Tiernan (the big liquid chlorine manufacturer) in August 1917. However, Alberto Portocarrero, president of the now-municipal Compañía de Acueducto de Bogotá, said there was not enough information to make that decision, and asked for a recommendation to the Colombian consul in New York, who took a long time replying. Desperate, a group of engineers led by Eugenio Díaz Ortega, a passionate defender of chlorination, travelled to New York, gathered information, and convinced the consul to send a positive recommendation on August 29, 1918. This recommendation only stirred things up.

Portocarrero replied that chlorination was not as cheap as advertised, as it would require new facilities that the city could not afford. Cenón Solano, director of the Hygiene and Sanitation Department of Bogotá, added that the repair of the equipment would have to be done in the United States, thus increasing the costs. He proposed studying alternative methods, including ultraviolet light, used at soda factories in Bogotá. Díaz Ortega accused Solano of suggesting useless alternatives, as ultraviolet light was tremendously more expensive than chlorine. Both of them and Portocarrero exchanged accusations and arguments in the newspapers in the following two years, with no apparent resolution.

Dr. Pablo García Medina, first director of Colombia’s Dirección Nacional de Higiene. Wikimedia.

The controversy ended somewhat abruptly in 1920, as after the 1918 Spanish Flu ravaged the city, the national government reformed Bogotá’s health institutions, centralising decision-making and increasing the hygiene budget. Pablo García Medina, leading the National Direction of Hygiene, backed chlorination in the Bogotá newspaper El Tiempo in 1920, arguing that liquid chlorine could be imported at a ‘really insignificant amount,’ making it possible to produce drinking water at a significantly lower cost than with Pearson’s proposal.

The previous examples show that technological imitation can occur through many means, including replicating experiments learned in academic journals, adopting techniques that seem to be having success elsewhere and reported via reports, diplomatic cables, exchanges with foreign experts, or evaluating and purchasing options available in the market. One or several of these took place in Jersey City, London and Bogotá, despite their institutional and economic differences.

Even Jersey City, the pioneer, imitated as it was relying on European experiments. Fertile ground for imitation grew as did global scientific and commercial connections. US doctors knew about Houston’s experiments with storing, and he was aware of recent chlorination success in American cities. Bogotá had ties to British engineering companies, and Colombian doctors were familiar with medical and engineering developments in Europe and the US, as they often were trained there.

Imitation did not preclude the agency of local actors, something clear in the case of Colombian doctors actively pursuing or rejecting chlorination. There was no passive attitude or mere uncritical copying of US technology there. Imitation is not simple; it requires rigorous evaluation and selection of alternatives, and it does not entail the straightforward adoption of foreign technology. It involves, as this case makes clear, reaching consensus amid fierce disagreement.

Edisson Aguilar Torres

King’s College London

How to cite this paper:

Aguilar Torres, Edisson. Water clorination. Sabers en acció, 2025-09-24. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/water-chlorination/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Recommended reading

Aguilar, Edisson, ‘Toward a Symmetrical Global History of Technology: The Adoption of Chlorination in Bogotá, London, and Jersey City, 1900-1920’, Technology and Culture 65 (2024) 4, 1195-1221.

Studies

Bakker, Moses Nelson, The Quest for Pure Water: the history of water purification from the earliest records to the twentieth century, (Denver, 1981).

Colón Llamas, Luis Carlos. “Ingeniería, medicina y urbanismo: El papel de las ideas higienistas en los cambios urbanos de Bogotá en la primera mitad del siglo XX.” In Ruben Mejía Sierra (ed.) La hegemonía conservadora, (Bogotá, 2018), 439–505.

Felacio Jiménez, Laura Cristina, El acueducto de Bogotá: Procesos de diferenciación social a partir del acceso al servicio público de agua, 1911–1929, (Bogotá, 2017).

Foss-Mollan, Kate, Hard Water: Politics and Water Supply in Milwaukee, 1870–1995 (West Lafayette, 2001).

Jones, Emma, Parched City: A History of London’s Public and Private Drinking Water, (Zero Books, 2013).

Melosi, Martin, The Sanitary City: Environmental Services in Urban America from Colonial Times to the Present, (Pittsburgh, 2008).

O’Toole, Colleen K., “The Search for Purity: A Retrospective Policy Analysis of the Decision to Chlorinate Cincinnati’s Public Water Supply 1890–1920,” (Ph.D. diss, University of Cincinnati, 1986).

Tarde, Gabriel, The Laws of Imitation, (New York, 1903).

Sources

Documentary History of American Water-works: http://waterworkshistory.us/

Registro Municipal de Higiene de Bogotá: https://catalogoenlinea.bibliotecanacional.gov.co/client/es_ES/search/asset/199783/0

Diario El Tiempo (Colombia): https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=N2osnxbUuuUC

L. Leal, “The Sterilisation Plant of the Jersey Water Supply Company at Boonton, N.J.,” in Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth Annual Convention of the American Water Works Association Held at Milwaukee, Wis., June 7–12, 1909, 104, Documentary History of American Water-Works, http://www.waterworkshistory.us/NJ/Jersey_City/1909AWWALeal.pdf