—A feminist category for rethinking knowledge(s) in a world in crisis.—

The COVID-19 pandemic showed us to what extent our survival as a species relies not only on the care we receive, but also on the care we provide to others, from the beginning of our existence until its end. While in lockdown, at 8pm each evening, we applauded the overwhelmed healthcare staff who were working in hospitals, caring for those patients suffering from the acutest symptoms of – what was still at that time – an unknown emerging infectious disease. During those days, we became aware that doctors were not the only workers who were fundamental for sustaining the social fabric; nurses, cleaners and supermarket cashiers were also on the frontline responding to the most basic needs of the population. Although the media praised them as heroes, paradoxically these essential workers were employed in some of the most underpaid sectors of the labour market because of the inherent gender, class and racial inequalities in our capitalist societies.

Painting for Saints or Game Changer. Banksy, 2020.

Feminist scholars and activists remind us that the devaluation of care is a result of its historical association with activities which have been traditionally performed by women in the private sphere, in line with the fixed gender roles defined by the nineteenth-century cult of domesticity. Furthermore, the progressive externalisation and commodification of care contributed not only to the feminisation, but also to the racialisation of care-related activities in the Global North. Despite the lack of recognition for caring work, crises – such as epidemics – tragically reveal that this remains a central part of our lives. We, humans, are not isolated individuals but rather interconnected beings, united by our shared vulnerability and responsibility for helping those of our fellows who are in distress.

From a feminist perspective, care not only represents a powerful ethical and political concept for rethinking justice in our democracies, it is also a useful category for widening the scope of the history of science, medicine and technology through the study of the often-invisible work carried out by numerous anonymous women in times of crises. Thus, care – as a historiographical category of analysis – enables us to rectify the androcentric vision which has dominated the history of humanitarian relief by examining the crucial role played by female agents in the emergence and further expansion of this movement from the late-eighteenth century onwards. Theorised by Berenice Fisher and (1990) as “a species activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, to continue, and to repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible”, care also provides a productive analytical tool for epistemologically approaching the plurality of women humanitarians’ relief activities as an ensemble of practical knowledge(s) that have remained at the margins of the history of medical humanitarianism.

Women humanitarians have been associated with stereotyped images, widely disseminated on Red Cross posters throughout the world wars, which portrayed them as heavenly nurses and/or compassionate mothers. This is due – in great extent – to the legacy of influential figures such as the British founder of modern nursing, Florence Nightingale (1820–1910), who implemented a health-care reform in the Scutari Hospital during the Crimean war (1854–1856). Despite Nightingale’s leading role in humanising the universe of warfare, most women humanitarians were not professional nurses. They were volunteers who had only been given a very rapid nursing training course, as in the case of the Genevan novelist Hélène Pittard-Dufour (1874–1953) who assisted wounded and ill soldiers during the First World War (1914–1918). Other female humanitarian representatives learnt about women’s health issues through their missions, such as the Swiss schoolmistress Elisabeth Eidenbenz (1913–2011) who specialised in obstetrics as the director of Elne’s maternity home – a centre which was settled in a little village in the South of France. In this centre, she helped Spanish, Jewish and Roma mothers who had been resettled in internment camps in the French Roussillon during the Second World War (1939–1945) to give birth to their children.

Photograph of the Swiss maternity home. Elne, France. Château d’en Bardou. Author: Dolores Martín-Moruno, 2017.

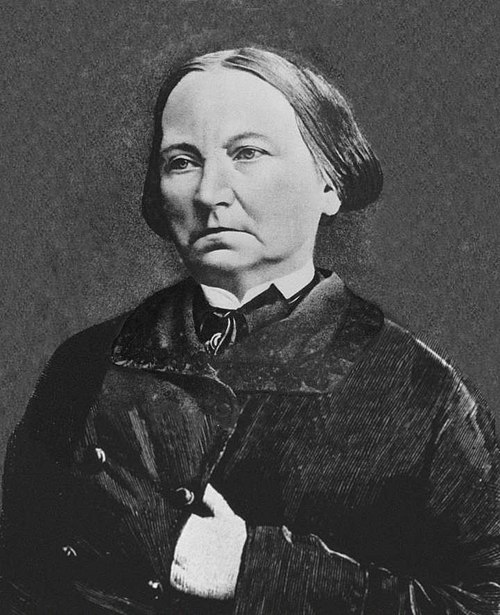

Throughout the major conflicts of the first half of the twentieth century, women humanitarians were rarely professional physicians, apart from a few figures who dared to defy the sexual division of labour which governed the field of operations. For instance, the British doctor and pacifist Hilda Clark (1881–1955) ran the maternity hospital at Chalons-sur-Marne during the First World War and the Spanish surgeon María Gómez Álvarez (1914–1975) worked at the Varsovia Hospital in Toulouse to improve the conditions of refugees who had fled from Spain after the Republican exile. Women humanitarians were often all-round activists, such as the Spanish writer Concepción Arenal (1820–1893) who advocated for a plethora of causes: the abolition of slavery and prostitution, prison reform, women’s right to education and the promotion of the Spanish Red Cross (SRC) since its inception. After she was appointed General Secretary of the SRC’s Ladies central section at the outbreak of the Third Carlist War (1872–1876), Arenal managed a hospital set up in Miranda del Ebro which relieved wounded soldiers from both warring parties.

Concepción Arenal (1820-1893). Wikimedia.

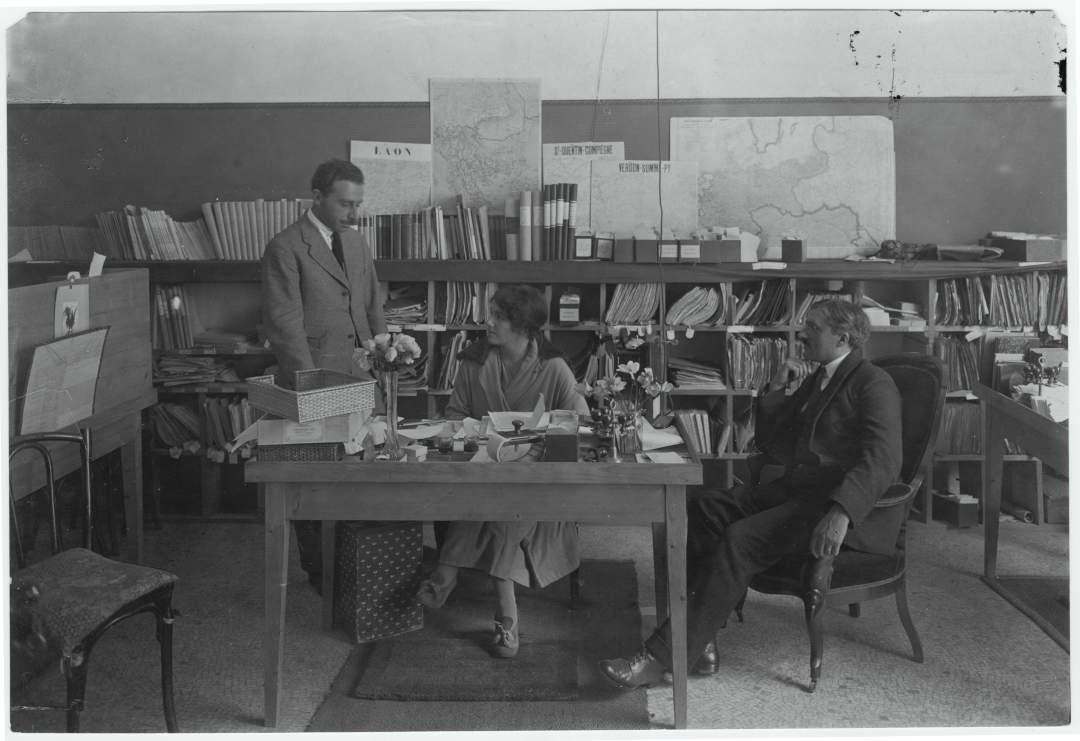

Women humanitarians also joined other transnational female networks such as those created by the war godmothers from Argentina, Canada, France, Spain and Switzerland. Throughout the Great War, they sent letters and parcels to emotionally support the Belgian soldiers who felt what was known as the blues of the trenches (in French: ‘le cafard’). War godmothers were not the only women humanitarians who cared for the victims of warfare at a distance, as shown by initiatives organised by Marguerite Frick-Cramer (1887–1963) and her colleague Marguerite van Berchem (1892–1984) for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) between the First and the Second World War. Their work focused on the emotional and material well-being of prisoners of war through innovative administrative and communication practices. Both women contributed to launching the International Prisoners of War Agency (IPWA) which reconnected families separated by war by processing vast amounts of information to identify and trace prisoners. Frick-Cramer applied her legal expertise to advocate for better protection for civilian detainees and led the Service for Dispersed Families during World War II. She was also the first woman to join the ICRC board, breaking gender barriers in a male-dominated institution.

Van Berchem, using the linguistic and cultural knowledge which she had acquired as an archaeologist working in North Africa, established the Colonial Service in 1949 to support indigenous soldiers with tailored assistance. Her work – like that of her colleague Frick-Cramer – emphasised the mental and emotional health of detainees, addressing issues such as Stacheldraht-Krankenheit, or ‘barbed-wire disease’, which was caused by isolation and uncertainty. This condition was identified by the ICRC delegate Adolf Lukas Vischer (1884–1974) who observed prisoners suffering from apathy, boredom and distress due to prolonged detention. His research highlighted the importance of maintaining communication with families to alleviate psychological suffering. Frick-Cramer’s and van Berchem’s commitment to care extended beyond immediate medical needs, highlighting the importance of caring at a distance which in this case meant using information networks and administrative tools to maintain prisoners’ connections with their families. Their contributions reflect the gendered dynamics of humanitarian history and the critical role of care work beyond traditional clinical settings.

World War I. Geneva, Musée Rath, Central Bureau of the Sections of the Entente at the International Prisoners of War Agency. Marguerite Frick-Cramer (center) with her colleagues Jacques Chenevière (left) and Etienne Clouzot (right). ICRC, V-P-HIST-03557-05.

Thinking about care beyond present-day medical and health-care professions provides a valuable historical perspective on a wide range of relief activities that were not solely aimed at healing wounds and diseases, but also at improving the health-care conditions of those in need and particularly their emotional well-being: a key concept in our current understanding of mental health. Moreover, the development of a history of care offers a privileged perspective for restoring women humanitarians’ knowledge(s) and, therefore, for acknowledging their collective authority within the history of global health. Even before the creation of international agencies such as the WHO, women humanitarians successfully transformed health into a transnational and transdisciplinary issue by caring for a world in crisis.

Although care has been historically defined as a female occupation, with women often imagined as being more naturally inclined toward tender feelings such as love and compassion, a gendered analysis allows us to deconstruct these stereotypes and recognise the complexity of caring activities. Moral concern and the display of feelings is required to alleviate others’ suffering, however it is also necessary to have concrete knowledge of these people’s situations so as to plan effective ways to improve them. Furthermore, care often involves performing dirty work involving repetitive and unpleasant tasks, as well as evaluating their reception by the care receivers. Thus, the production of care challenges dichotomic divisions between reason and emotion, work and labour.

Even though those who care are still predominantly women, more Feminist research is needed to include the study of masculinities within this area. This is more urgent than ever, as care should matter to all global citizens living in a world that is constantly being reshaped by crisis upon crisis due to pandemics, wars, and also climate change.

Dolores Martín-Moruno

IMF-CSIC

Valérie Gorin

University of Geneva

How to cite this paper:

Martín-Moruno, Dolores, and Gorin, Valérie. On care. Sabers en acció, 2025-03-05. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/on-care/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Recommended reading

Valérie Gorin and Dolores Martín-Moruno. “Caring for prisoners of war: Marguerite Frick-Cramer’s and Marguerite van Berchem’s service activities in the International Committee of the Red Cross (1914–1969),” Dynamis 44 (1), 2024: 29-52.

Dolores Martín-Moruno, Camille Bajeaux and Valérie Gorin, “What is the history of care the history of?”, Dynamis 44 (1), 2024: 13-14 https://raco.cat/index.php/Dynamis/article/view/429936/524273

Studies

Jon Arrizabalaga, “The ‘merciful and loving sex’: Concepción Arenal’s narratives on Spanish Red Cross women’s war relief work in the 1870s,” Medicine, Conflict and Survival 36 (1), 2020: 41-60.

Jon Arrizabalaga and Álvar Martínez-Vidal. “Las mujeres en los servicios sanitarios de los frentes de guerra y de la retaguardia (1914-1945)”. In: Mujeres y niños en una Europa en guerra (1914-1949), Alicia Alted, Luiza Iordache and Laura López (eds.), 175-185. Madrid: Círculo de Bellas Artes de Madrid, 2021.

Berenice Fisher and Joan C. Tronto. “Towards a Feminist Theory of Caring”. In Circles of Care: Work and Identities in Women’s Lives, Emily K. Abel and Margaret K. Nelson (eds.), 35-62. New York: State University New York Press, Albany, 1990.

Marie Leyder. “Santé et pratique épistolaire pendant la Première Guerre mondiale. Lettre d’un soldat à son ancienne infirmière et marraine de guerre,” Histoire, médecine et santé, 23, 2023: 87-92.

Dolores Martín-Moruno. Beyond Compassion: Gender and Humanitarian Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023. https://www.cambridge.org/core/elements/beyond-compassion/261099F86D37CADD03F22E2BD16E4C94?utm_campaign=shareaholic&utm_medium=copy_link&utm_source=bookmark

Esther Möller, Johannes Paulmann and Katharina Storning. Gendering Global Humanitarianism in the Twentieth Century: Practice, Politics and the Power of Representation. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

Dolores Martín-Moruno. Beyond Compassion: Gender and Humanitarian Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023. https://www.cambridge.org/core/elements/beyond-compassion/261099F86D37CADD03F22E2BD16E4C94?utm_campaign=shareaholic&utm_medium=copy_link&utm_source=bookmark

Dolores Martín-Moruno. “Elisabeth Eidenbenz’s humanitarian experiences during the Spanish Civil War and Republican Exile,” Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, 21 (4), 2020: 485-502.

Dolores Martín-Moruno, “A female genealogy of humanitarian action: compassion as practice in the work of Josephine Butler, Florence Nightingale and Sarah Monod,” Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 36 (1), 2020: 19-40.

Dolores Martín-Moruno, Brenda Lynn Edgar and Marie Leyder. “Feminist Perspectives on the History of Humanitarian Relief”, Medicine, Conflict and Survival 36 (1), 2020: 1-17. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/13623699.2020.1717720?needAccess=true

Àlvar Martínez-Vidal. “The powers of masculinization in humanitarian storytelling: the case of the surgeon María Gómez Álvarez in the Varsovia Hospital (Toulouse, 1944–1950),” Medicine, Conflict and Survival 36 (1), 2020: 103-121.

Najat Vallaud-Belkacem and Sandra Laugier. La société des vulnérables. Leçons féministes d’une crise. Paris: Gallimard, 2020.

Websites and other sources

Kim Adams and Saronik Bosu, “Care Ethics”. A Discussion with Merel Visse and Inge van Nistelrooij. High Theory. New Books Network. https://newbooksnetwork.com/care-ethics

“Invisible Figures: Women’s Legacy in Humanitarian Action” Blog of the Geneva Centre of Humanitarian Studies, Faculty of Medicine, University of Geneva. https://humanitarianstudies.ch/invisible-figures-womens-legacy-in-humanitarian-action/

Marie Leyder, “Who was Maria Eskens (1892-1989)”, International Red cross and Red Crescent Museum. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jvR0JKncm7g

Dolores Martín-Moruno and Alexandra Calmy “Au-délà de la compassion : Genre et action humanitaire”, Colloques Institut Éthique Histoire Humanités, October 2023. https://mediaserver.unige.ch/play/200908

Dolores Martín-Moruno, Brenda Lynn Edgar and Marie Leyder, Website “Beyond Compassion”. https://beyondcompassion.ch/en/about-us/

Dolores Martín-Moruno, “Who was Sarah Monod (1836-1912)”, International Red cross and Red Crescent Museum. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CppbOSvYWck&t=4s

Dolores Martín-Moruno, “Who was Salaria Kea (1913-1991)”, International Red cross and Red Crescent Museum. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=blY599I3Yas&t=1s

“Who Cares? Gender and Humanitarian Action”. International Red cross and Red Crescent Museum. https://redcrossmuseum.ch/archives/who-cares-genre-et-action-humanitaire/?lang=default