—Two figures in international health and medical humanitarianism in the years of the Second World War.—

The generation of doctors who practised their profession during the interwar period (1914-1945) showed a special sensitivity to the social implications of health and displayed a strong commitment to military and political events that directly affected them. The dismemberment of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the decline of the British Empire, the crisis of colonialism, the two World Wars, the Great Depression, the rise of Nazism and the workers’ revolutions disrupted world geopolitics and gave way to the period of the Cold War. The scientific and technical development of medicine, its internationalisation and its participation in these events were not unrelated to the international shifts.

Ludwik Rajchman (1881-1965). Sousa Mendes Foundation.

A prominent protagonist of this international health movement was specifically Ludwik Rajchman (1881-1965), a Polish doctor who, after graduating in Krakow, specialised in microbiology in the laboratory of Ilya Metchnikof at the Pasteur Institute (Paris). Later he was professor of bacteriology at King’s College (London) between 1910 and 1913 and, at the beginning of the Great War, he directed the Central Dysentery Laboratory (London), where he coordinated strategies against the Spanish flu and polio, two great tragedies that spread with the end of the war. In 1918 he returned to Warsaw to found the National Institute of Hygiene and the National School of Public Health (1923), both funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. Rajchman was a great promoter of international health during his time as director of the Health Organization of the League of Nations. From this vantage point he promoted the creation of international networks of health cooperation in various areas. He began an intense campaign of health diplomacy in the face of the aftermath of war, famines, the transit of refugees, the fight against typhus epidemics, agreements on biological and serological standards, being the real driver of the joint programme that the League of Nations launched with the support and funding of the Rockefeller Foundation. His personal involvement made him travel to China for two years as an advisor to the Chang Kai-shek government, promoting an international advisory council on health matters.

Palais des Nations (Ginebra). League of Nations Archives.

The advance of fascism forced Rajchman to leave the League of Nations in 1939, but, even then, with the support of Jawaharlal Nehru, he organised an international conference for peace. Between 1939 and 1941 he was appointed delegate for humanitarian affairs of the Polish government in exile, and in 1943 he participated in the creation of UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration) which provided medical and food aid for war-torn countries. When in 1947 the UNRRA was liquidated, with the support of former President Herbert Hoover, Rajchman promoted a special fund for international aid for children: UNICEF (United Nations’ International Children’s Emergency Fund), of which he was the first chairman, urgently taking responsibility for the distribution of antibiotics, milk powder and vaccination campaigns against tuberculosis, among others. With the tensions arising from the Cold War, Rajchman’s position became complicated. In the Eastern bloc he was suspected of being a pro-American agent and, as a result, his Polish diplomatic passport was confiscated. While in the United States, in the midst of the persecution of communism, McCarthy’s followers accused him of being a communist spy. In 1957 he was forced to leave America and never returned, settling permanently in France. In Paris, he founded the International Center for Childhood (ICC) with Roger Debré to train public health workers from poor or warring countries in social paediatrics. He died in 1965 in Chenu (France) and the speakers at his funeral were two of the great figures of Europeanism: Jean Monnet and Roger Debré. Half a century after his death, Ludwik Rajchman’s tireless activism for global health deserves the recognition he never received.

Walter Cannon (1871-1945). Wikipedia.

For his part, the American doctor Walter Cannon (1871-1945), professor of physiology at Harvard University, was not only a great scientist and researcher, but also stood out for his commitment to international political activism and the defence of human rights. For two decades he carried out his first research on the physiology of emotions between 1897 and 1911. His studies show that emotion activates both the autonomic nervous system and adrenaline, thus provoking a state of stimulation that can turn into a reaction of alarm similar to that provoked by a threat or fear. At the end of the Great War, in 1917, Cannon joined the American army. He then worked as a doctor in field hospitals in England and France, and there he could observe the triggering of traumatic shock and the concatenation of the physiological phenomena that provoke it. After the war he returned to Harvard to concentrate on analysing the complexity of chemical neurotransmission. It was then that he proposed the concept of homeostasis (1926), key to understanding the mechanisms of organic regulation, which developed Claude Bernard’s initial idea about the ‘milieu intérieur’ or internal medium. The concept of homeostasis became a fundamental paradigm of life sciences to understand and analyse the idea of organic integration. His studies on emotions and his notion of homeostasis opened the doors to the development of psychosomatic medicine.

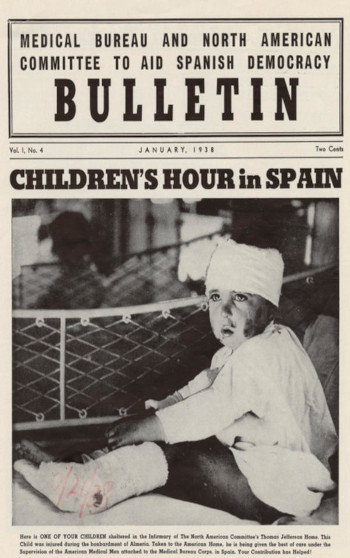

Cover of the Medical Bureau and North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, January 1938. Pinterest.

In addition to this facet as scientist and researcher, it is also important to recognise that Walter Cannon as well became an important public figure in the domain of international medical politics and activism. During his involvement as a doctor during the war he had experienced the threat of fascism first-hand in Europe, and maintained a close relationship with researchers from all over the world, including the Spanish physiologist Juan Negrín, who he met in Leipzig when Negrín was a young disciple of Theodor von Brücke and a researcher at the most famous Institute of Physiology in Germany. Walter Cannon was aware of the drama threatening the Spanish Republic, and of the link between Franco’s military coup of 1936 and the advance of international fascism. This is why he actively participated in organisations that helped refugee doctors; he chaired the American Medical Bureau to Save Spanish Democracy and the American-Soviet Medical Society. Unlike the growing anti-communism that spread among American conservatives, Walter Cannon always defended freedom and social commitment, refusing to accept undemocratic authoritarian positions. Together with Edward Barsky and other doctors, he became actively involved in the Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish War, very critical of the intolerable neutrality of the US government. Cannon represents the character and values of the purest honourable scientist, not only for his unquestionable contribution to science, but also for his political commitment to the values of freedom and human rights.

Josep Lluís Barona Vilar

IILP-UV

How to cite this paper:

Barona Vilar, Josep Lluís. Biographies: Ludwick Rajchman and Walter Cannon. Sabers en acció, 2021-02-10. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/biographies-ludwick-rajchman-and-walter-cannon/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Recommended reading

Barona Vilar, J.L. The Rockefeller Foundation, International Diplomacy and Public Health. London: Pickering & Chatto; 2015.

Borowy, I., Coming to Terms with World Health. The League of Nations Health Organization 1921-1946, Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lange, 2009.

Brunton, D. (ed.) Health, disease and society in Europe. A source book. Manchester: Manchester University Press / Open University; 2004.

Weindling, P. (ed.), International Health Organisations and Movements, 1918–1939, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995.

Studies

Balinska, Marta A. For the Good of Humanity: Ludwik Rajchman, Medical Statesman (Translated by Rebecca Howell). Budapest: Central European University Press, 2004.

Barona, J.L.; Bernabeu Mestre, J. La salud y el estado. El movimiento sanitario internacional y la administración española (1851-1945). Valencia: PUV; 2008.

Brooks, Ch.C.; Koizumi, K; Pinkston, J.O. The life and contributions of Walter Bradford Cannon 1871-1945. New York: State University of New York; 1972.

Cueto, M. (ed.), Missionaries of Science: The Rockefeller Foundation and Latin America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1994.

Löwy, I. and Zylberman, P. “Introduction. Medicine as a Social Instrument: Rockefeller Foundation, 1913–45”, Studies in the History and Philosophy of Biology and Biomedical Sciences 31:3 (2000), 365–379.

Palfreeman, L. ‘Salud! British Volunteers in the Republican Medical Service during the Spanish Civil War’. Sussex: Academic Press/Cañada Blanch Centre for Contemporary Spanish Studies; 2012.

Wetherby, A. The Medical Activists: Humanitarians, Activists, and American Medical Relief to Spain and China, 1936-1949, Unpublished PhD Thesis, Oxford, 2014.

Wolfe, E. L. Walter B. Cannon, Science and Society. Boston: Harvard University Press; 2000.

Zunz, O. Philanthropy in America: A History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Sources

Cannon, W.B. The wisdom of the body. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.1939.

Ludwik Rajchman Lecture before the Royal Society of Medicine, 9 April 1924. Archives of the League of Nations, Dos. 34707, 1924, 1 doc, cart. 931.

Melville D. Mackenzie, Medical Relief in Europe. Questions for Immediate Study. London, Oxford University Press, 1942.