—The transformation of the regime of knowledge production, and history as a tool to reflect on the present and future of science.—

The history of science is a relatively young branch of historiography, but with a wide and varied tradition, as seen in previous sections. In fact, in their eagerness to understand the historical evolution of the sciences, professionals in the discipline have tried to characterise the way in which scientific knowledge has been produced using various approaches. Among the most recent approaches are those of the French science historian Dominique Pestre, who, in the framework of his studies on the relationships between politics, markets and the construction of scientific knowledge, developed the notion of a ‘regime of knowledge production’. This concept refers to the different elements, including institutions, beliefs, practices and political and economic regulations, that define the place and way of being of science, making it a dynamic category, with a complex structure and without strict or predetermined rules that can only be described according to a historical perspective.

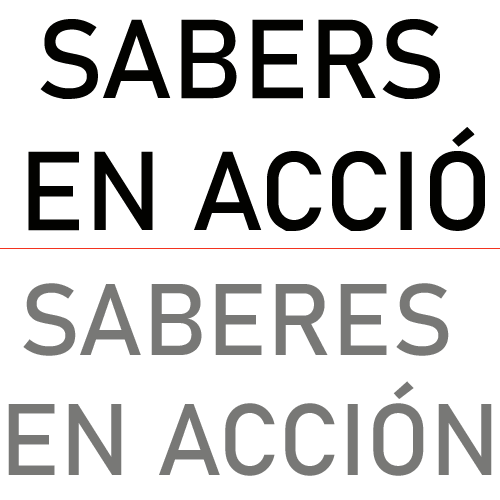

Hydraulic pressure tests for cast steel shells (1916). Ministère de la Culture (France).

The existence of different regimes of knowledge production throughout history makes it possible to represent great variations in the way of the production of scientific knowledge and its relations with society. These are complex processes that are carried out continuously through elements whose relationships are reconfigured over time. For example, far from accepting that science enjoyed autonomy and independence until the final decades of the twentieth century, research in the history of science shows how the creation and circulation of scientific knowledge has been, at least since the Renaissance, closely related to political and ideological motivations, as well as to economic factors of various kinds. In other words, scientific, medical and technological development has been shaped by a historical context in which various factors have intervened, including hegemonic discourses, social values, prevailing practices and norms, political regulations, etc. For the history of science, therefore, the analysis of the changing ways of articulating and regulating scientific production to think historically about changes in the regime of knowledge production is very relevant.

Bell Aircraft Corporation fighter aircraft production line at Wheatfield, New York (1940-1945). Wikimedia.

Under these premises, it is possible to address the complex and variable relationships between science and political and military power, links that have existed for a long time, but which were redefined throughout the twentieth century to acquire their own distinguishable characteristics. There is no doubt that the two great wars of the twentieth century allow us to see in more detail the way in which the links between techno-science and the military industry were established. On the one hand, the First World War, characterised as a large-scale industrial war between industrialised nations, marked the birth of a military-industrial complex that served as a stimulus for the modern corporate economy. It is not surprising that ammunition producers such as Brunner, Mond and Nobel had a huge injection of state funds. It was beginning to become clear how public investment in science guaranteed the nations’ profits.

“Mighty Atoms”, illustration published in the Chicago Tribune in 1945. Nuclear Secrecy.

Similarly, the Second World War played a decisive role in the image that was projected and the importance that science and scientists acquired. In fact, at the end of the conflict, research for military purposes was consolidated and institutionalised, in order to achieve the technological superiority that science offered and that was able (or at least perceived) to ensure military domination. This was something that many scientists and academic leaders welcomed, since it represented an important injection of financial resources for research, at the expense, however, of blurring the boundaries between civil and military research. In this sense, the arms industry partially merged its objectives and procedures with those of scientific and technological research, with the approval of the latter.

In the last decades of the twentieth century, all these factors led to a transformation of the regime of knowledge production that altered the balance between public science and private and industrial science. The rise of financial markets and the emergence of new supranational bodies not only diminished the functions of States and changed traditional legitimacy mechanisms, but also turned techno-science, organically linked to the industrial world, into a financial asset to be controlled in order to succeed. Understanding the way in which these relationships and alliances between science and technology and political and economic powers have historically been articulated also allows us to better understand the world in which we live, while at the same time serves to raise a final reflection about the purpose of history. As the chapters dedicated to other eras show in various ways, historical knowledge can be tremendously useful in shedding light on debates on state policies and existing legislation. History makes it possible to identify current events in the framework of long-lasting processes, often affected by great complexity, under pressure from political and economic interests, as well as very diverse social and cultural forces. Historical analysis allows the search for patterns, ruptures and continuities, the integration of multiple contexts and the study of complex interactions between different societies and cultures with the science, technology and medicine of each period. In this way, through the study of complexity, many myths can be questioned that prevent us from properly thinking about the situations of the present. In addition to openly scientific approaches and the ideology of modernisation, the mythology of scientific knowledge remains present in many discourses, as well as in informative and teaching texts. These are images that implicitly convey a whole series of conceptions and values about science, technology and medicine and their relationships with society, most of which have been questioned, if not openly rejected, by academic research.

“Report on the atomic bomb, the greatest achievement in history, the result of the combined efforts of science, industry, labour and the military”, by Clifford Berryman (Paperless Archives, 1945). Paperless Archives.

The Knowledge in Action project seeks to dismantle the most frequent myths about science and to present new accounts, figures, spaces and problems, more in line with recent trends in historical research. Through this long journey in time, from the ancient world to the present day, it has become clear that science, technology and medicine are social activities whose development responds to norms and values characteristic of specific historical environments. They are ways of knowing and doing closely linked to social, political and cultural features that also contribute to shaping it. The chapters of the second volume of the project will offer more examples in this direction through several cross-cutting themes over a long period. In this way, through this double chronological and thematic approach, the Knowledge in Action project makes it possible to establish a productive dialogue between the past and present of science, technology and medicine. History allows us to better explore, analyse and understand the co-production of all these activities and, in this way, offers elements to critically reflect on many of the problems of the present and try to imagine a better future.

Pedro Ruiz-Castell

IILP-UV

How to cite this paper:

Ruiz-Castell, Pedro. Contemporary science. Sabers en acció, 2021-02-26. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/contemporary-science/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Recommended reading

Joerges, Bernward; Shinn, Terry. Instrumentation Between Science, State and Industry. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001.

Nowotny, Helga; Scott, Peter; Gibbons, Michael. Re-thinking science. Knowledge and the public in an age of uncertainty. Londres: Polity Press; 2001.

Nowotny, Helga; Pestre, Dominique; Schmidt-Assmann, Eberhard; Schulze-Fielitz, Helmuth; Trute, Hans-Heinrich. The public nature of science under assault: Politics, markets, science and the law. Berlín: Springer; 2005.

Pestre, Dominique. Ciencia, dinero y política. Buenos Aires: Nueva Visión; 2005.

Pickstone, John V. Ways of knowing: A new history of science, technology and medicine. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000.

Other sources

González Silva, Matiana. ¿Con quién dialoga Dominique Pestre? El papel de la historia en los debates sobre la ciencia contemporánea. Dynamis. 2007; 27: 359-367.

Levin, Luciano; Pellegrini, Pablo A. Notas críticas sobre los estudios en ciencia, tecnología y sociedad: entrevista a Dominique Pestre. Networks. 2011; 17 (33): 95-106.

Pestre, Dominique. La production des savoirs entre académies et marché, une relecture historique du livre The New Production of Knowledge. Revue d’économie industrielle. 1997; 79: 163-174.