—A biography to reflect in the importance of hygiene for health.—

Until the mid-nineteenth century, one of the main complications after childbirth was called postpartum sepsis or postpartum infection. Once the placenta is detached, the vessels in the uterine wall where it was attached remain open until they contract. During this time, it is possible for germs from the hands of the person caring for the woman in childbirth to enter the body through them, resulting in widespread infection and often death if proper treatment is not applied. In the last decades of the eighteenth century, obstetricians Charles White in Manchester and Joseph Clark and Robert Collins in Ireland had already drastically reduced the incidence of this complication by washing the hands of all staff caring for the woman in labour, limiting vaginal examinations during childbirth, the ventilation of the rooms and the continuous cleaning of the delivery room, as well as of the beds and sheets. Their hygienic practices had hardly any followers

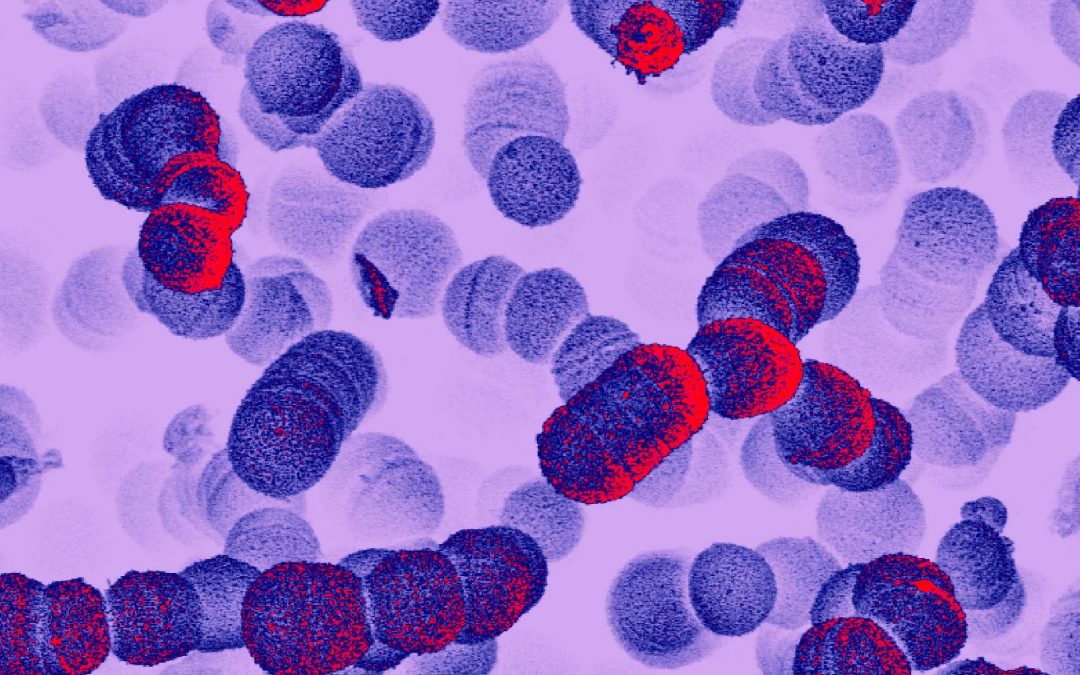

Streptococcus (David Goulding, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute). Wellcome Collection.

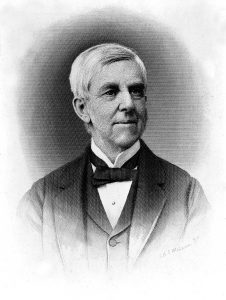

The American Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-1894), in the course of a lecture given in 1843 in Boston before the Society for the Progress of Medicine, suggested that puerperal sepsis was an infectious disease transmitted by people who cared for the woman during childbirth. To avoid it, he suggested that medical personnel should allow at least one day between performing an autopsy on a woman who died of puerperal sepsis and attending a delivery. He also urged frequent changing of clothes and hand washing with a calcium hypochlorite solution. He spread his method through his work The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever, published that same year. His idea was not accepted and it was even considered an insult to claim that doctors could transmit an infection.

Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever. Cover of the work by I. Semmelweis. Semmelweis University.

Three years later, the Hungarian obstetrician Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865) observed a large disparity in the mortality of women admitted to two maternity wards at the Vienna General Hospital where he worked. Ward I was attended by doctors and medical students and mortality ranged from 10 to 20 per cent. On Ward II, attended by teachers and midwifery students, mortality was reduced to 3%. The type of care provided in the two clinics was similar. The only difference was that midwives did not do autopsies. This disparity was well known to the women in labour attending the hospital. These were poor women who opted for free care in exchange for allowing medical students and midwives to carry out their placement with them. Admission to one or the other clinic was made on alternate days and women begged not to be admitted to Ward I for fear of dying shortly after giving birth. Semmelweis also noted that women who entered late having already given birth at home or in a car rarely became ill with puerperal fever. It seemed, therefore, that the infection was contracted at the same time as birth.

Marble statue of Ignaz Semmelweis, by A. Strobl, located in the Szent Rókus Hospital in Budapest. Wellcome Collection.

The definitive proof of the origin of the infection was provided in 1846 by the death of a friend of Semmelweis, Jakob Kolletschka, a forensic doctor at the hospital. He died after suffering a generalised infection when his finger was pricked with a scalpel while performing an autopsy on a woman who died of puerperal fever. When the autopsy was performed, Semmelweis observed changes similar to those suffered by women with postpartum infection, a build-up of pus distributed throughout the body. He concluded that doctors and students who performed autopsies before going into labour carried the remains of the rotting flesh of the cadavers on their hands, where the infectious agent was thus transmitted to the women in labour.

Washing hands with soap and water did not completely remove the smell of the corpse, so Semmelweis thought that not all cadaverous particles were removed. In 1847 he ordered everyone who attended the delivery room, both doctors and students, to wash their hands with chlorinated water, a calcium hypochlorite solution used since the eighteenth century to eliminate the bad smell of rotting. One month later, mortality on Ward I was very similar to that observed on Ward II. After one year, mortality dropped to 1 per cent. Such solid results did not convince the head of the maternity ward for which he worked, Johann Klein, who disapproved of his practices and limited his clinical activity. Despite the support of his former professors at the Vienna Faculty of Medicine, pathologist Carl von Rokitansky and clinician Joseph Skoda, as well as dermatologist Ferdinand Hebra, Semmelweis was dismissed from the hospital in 1849 and returned to Hungary.

Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-1894). Wellcome Collection.

In Budapest, Semmelweis successfully applied his method, both in the obstetrics wards of St. Rochus hospital, as well as in the maternity unit of the university. In 1861 he published his book, Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever, which was received with hostility by the medical community. Figures of the stature of the pathologist Rudolph Virchow opposed his ideas. Semmelweis, a man of difficult character, could not accept the criticisms of his work. In 1865 serious dementia, perhaps due to tertiary syphilis, obliged Skoda to come to Budapest to transfer him to Vienna, where he was admitted to a clinic for the mentally ill. Semmelweis resisted internment and was severely beaten by the workers of the institution, who immobilised him with a straitjacket. They may have caused a wound, from which the gangrene resulted in his death three weeks later. For a long time, it was believed that before being transferred to Vienna, Semmelweis entered the anatomy dissection room of the University of Budapest and, in front of the students, opened a corpse with purulent lesions and pricked his finger with a scalpel. In any case, perhaps fate wanted him to die from the same disease he had tried to prevent, generalised sepsis, without achieving the spread of his antiseptic method.

The idea that it was the medical personnel themselves who could transmit certain infectious diseases, which were often fatal, was difficult to admit. There was a lack of a solid interpretation to support it and this was then the role of microbial disease theory in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The process was not simple, nor without controversy. In 1879, a conference was held at the Academy of Medicine in Paris, at which the gynaecologist Edouard Hervieux (1818-1905) harshly criticised the theory of germs as the cause of puerperal sepsis. One of the attendees interrupted him, went up to the dais and drew a row of dots on the board, saying: ‘Here are your germs, Sir.’ It was Luis Pasteur showing the streptococci, microorganisms that caused the postpartum infection according to the experiments he had just carried out. He was the first to reproduce them after isolating them from the blood of a puerperal fever patient and a new born with neonatal sepsis.

Mª José Báguena Cervellera

IILP-UV

How to cite this paper:

Báguena Cervellera, Mª José. Ignaz Semmelweis. Sabers en acció, 2021-01-18. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/ignaz-semmelweis-en/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Recommended reading

Loudon, Irvine. The tragedy of childbed fever. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000.

Nuland, Sherwin B. El enigma del doctor Ignaz Semmelweis. Fiebres de parto y gérmenes mortales. Barcelona: Antoni Bosch, editor; 2005.

Studies

Carter, K. Codell; Carter, Barbara. Childbed Fever. A Scientific Biography of Ignaz Semmelweis. London: Greenwood Press; 1994.

Obenchain, Theodore G. Genius Belabored. Childbed Fever and the Tragic Life of Ignaz Semmelweis. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press; 2016.

Sources

Holmes, Oliver Wendell. Puerperal Fever as a Private Pestilences. Boston: Ticknor and Fields; 1855.

Semmelweis, Ignaz. The Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever. Translated by K. Codell Carter. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press; 1983.

Websites and other resources

Fresquet Febrer, José L. Lavarse las manos. Ignaz Semmelweis [Updated May 2020: accessed 5 July 2020]. Available here.