—The psychological, social and political dimensions of illness.—

‘Health is more than the absence of disease: the word health implies something positive, that is, physical, mental and moral well-being. That is the goal we must reach, even if it goes beyond the possibilities of curative and preventive medicine.’ This phrase is part of the founding text of the World Health Organization in 1948 and reflects a programmatic idea of the Swiss health professional Raymond Gautier, acting director of the Health Section of the League of Nations between 1939 and 1942. Written in 1944, this statement by Gautier – who originally came from physiological laboratory research – assumed a basic principle: that disease is not just a loss of organic balance, called homeostasis, but also a psychological problem, a biographical fracture and a disorder in the social integration of the sick person. This multiple dimension of illness has numerous dimensions. Beyond the biological dimension, the Argentinian writer Adolfo Bioy Casares attributed a teleological sense to it when he states through one of his characters that ‘disease is the pretext that the body gives to die’. Much has been written about the meaning and sense of disease. The American writer Susan Sontag, in her essay Illness as Metaphor (1978) defined it as the night-side of life, the one that, sooner or later, we all have to face.

Portrait of the German physician, pathologist and anthropologist Rudolf Virchow (1821-1902). Wikipedia.

The German anthropologist, politician and physician Rudolf Virchow stated that ‘medicine is social science, and politics nothing more than medicine on a grand scale’ (1848). All these references express the extent to which disease has a psychological, social and political dimension. Disease sometimes manifests itself as a subjective perception, other times it arises as a result of a chance exploratory finding, or sometimes it presents itself as an unexpected accident. The affected person experiences some symptoms (discomfort, pain, fatigue, etc.) that healthcare personnel try to translate into signs of illness through exploratory tests (tests, X-rays, etc.) and all this always happens in a family and community environment that gives meaning to what happens. Depending on their condition and attitudes, the patient decides whether, despite his/her situation, he/she wishes to continue the normal life or whether, on the contrary, to assume the role of patient and follow a therapeutic itinerary by visiting the health centre, and perhaps suspending work activity. That is why disease can leave a biographical imprint beyond its bodily dimension. This is especially the case when serious diseases such as cancer, degenerative diseases, cardiovascular events, or certain diseases stigmatised by cultural values such as AIDS, tuberculosis or syphilis happen. Disease has not only an organic or biological dimension, but also a psychological, social and work dimension.

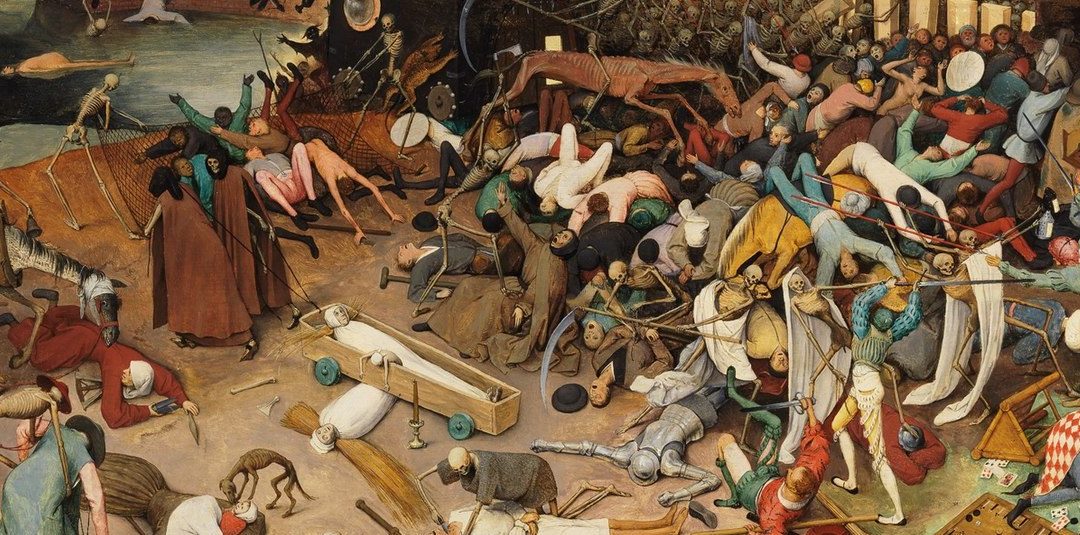

Beyond religious myths and literary legends about original paradises, which span all cultures, transporting time to a mythical past when human beings supposedly lived in harmony with the sacred order of nature, free from sin, disease and death, we certainly know that disease is consubstantial to life. Life is the real deadly disease, as the German poet Friedrich Hölderlin stated. But the way in which disease manifests itself in human communities is very diverse, depending on social and cultural factors. If in the Ancien Régime, the dominant diseases were infectious and caused great epidemic catastrophes such as plague or smallpox, which together with famines and wars were the cause of a very high death rate, on the other hand, in our post-industrial societies, the death rate is lower and is mainly caused by cancer, cardiovascular and traffic accidents, viral diseases, and others associated with ageing, environmental deterioration and habits: smoking, pollution, addictions, mental disorders. We see, therefore, that disease is a universal condition that manifests itself differently in different historical contexts and periods.

The Triumph of Death by Pieter Brueghel the Elder (ca. 1562). Museo del Prado. Wikipedia.

It is easy to understand that health is intimately related to lifestyle: diet, physical exercise, consumption of alcohol, tobacco, medicines, environmental and household hygiene… These are factors that are added to the predisposition that biological inheritance transmits. That is why information and education are essential. However, disease is also influenced by living conditions that are often also linked to social class and profession, climate and culture, which are different in every corner of the planet, in Mediterranean, Scandinavian, Asian or Central African societies. In addition, countries have established regulations to protect the health of the population, for example, by restricting the consumption of drugs, tobacco or alcohol, and legal regulations that establish the health conditions required in public establishments, working conditions, polluting industries and many others. All this defines a healthier or less healthy context, which determine the health conditions of a society.

Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Geneva, 1948) proclaims the universal right to health as follows: ‘Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing, medical care and necessary social services…’. The Universal Declaration was the result of a historic process in which, from the end of the nineteenth century on, the emancipatory struggles of workers and women, as well as social reformers provided a political response to the right to health, something that was reflected in the majority of democratic constitutions of nations. Especially in areas of industrial development and also in the cities, workers’ organisations promoted the first initiatives, ‘igualas’ insurance systems, mutual aid societies, which laid the foundations for the participation of the State and public administration in health care. The Prussian state of Bismarck, from the second half of the nineteenth century on, created a system of so-called Krankenkassen or sickness funds, and Tsarist Russia spread the Zetsvo system to provide assistance for peasants in the vast rural areas of Russia. They were the first steps of the so-called providential state, which, overcoming the idea of charity and hand-outs for the poor, tried to guarantee access to health and social protection against poverty and homelessness in contemporary societies from the end of the nineteenth century. However, it was from the Second World War (1945) on, that national health systems sought to universalise health care within the framework of the welfare state social model. Depending on the dominant model of political and economic organisation, a plurality of care systems emerged during the Cold War. Western Europe, Canada, Japan, Australia, New Zealand created state-funded public services. The British National Health Service (1948) was a pioneer and model to imitate. However, in the United States health care is still based on a service contract with private health insurance companies, so the state only intervenes in Medicaid, which is minimum health assistance for the unemployed and marginalised, and Medicare, basic assistance for pensioners. On the other hand, during the Cold War, the socialist bloc developed state models of health care, which, with the exception of Cuba and North Korea, collapsed with the crisis of the communist countries in the early 1990s and the globalisation of deregulated neoliberalism, which in many cases caused health chaos in a process of unplanned transition, where those then excluded from previous state protection were helpless. In addition, in most poor countries spanning large regions of Africa, Asia and Latin America, health care reflects inequality: traditional forms of folk medicine, quackery, magic religious practices and international humanitarian aid coexist with Western hospital centres for the elite and managers of multinational companies.

Josep Lluís Barona Vilar

IILP-UV

How to cite this paper:

Barona Vilar, Josep Lluís. The political economy of health. Sabers en acció, 2021-02-05. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/the-political-economy-of-health/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Recommended reading

Barona Vilar, J.L. Salud, tecnología y saber médico. Madrid: Ed. Fundación Ramón Areces; 2004.

Brunton, D. (ed.) Health, disease and society in Europe. A source book. Manchester: Manchester University Press / Open University; 2004.

Cooter, R.; Pickstone, J. (eds.) Companion to Medicine in the Twentieth Century. London and New York: Routledge; 2003.

Kiple, K.F. et al. (eds.) The Cambridge world history of human disease. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Rosen, George. From Medical Police to Social Medicine: Essays on the History of Health Care. New York: Science History Publ.1974.

Studies

Andresen, A., Groenlie, T.; Hubbard, W.; Ryymin, T. (eds.) Healthcare Systems and Medical Institutions. Oslo: Novus Press; 2009.

Barona, J.L. Health Policies in Interwar Europe. A transnational perspective. London, Routledge, 2019.

Barona, J.L.; Bernabeu Mestre, J. La salud y el estado. El movimiento sanitario internacional y la administración española (1851-1945). Valencia: PUV; 2008.

Bernabeu Mestre, J. Enfermedad y población, Valencia: SEC/Universitat de València; 1995.

Martínez Navarro, F. (ed.) Salud Pública. Buenos Aires: McGraw-Hill Interamerican; 1998.

National Health System, Spain 2010. Madrid, Ministry of Health and Social Policy; 2010.

Pons, J.; Silvestre, J (eds.) Los orígenes del Estado de Bienestar en España, 1900-1945: los seguros de accidentes, vejez, desempleo y enfermedad. Zaragoza: Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza; 2011.

Rosen, George. A History of Public Health. New York: MD Publ.;1958.

Vicens, J. El valor de la salud. Una reflexión sociológica sobre la calidad de vida. Madrid: Siglo XXI; 1995.

Sources

Gautier, R. Report on “International Health of the Future”, Rockefeller Archive Center [RAC], RG 1.1, series 100, box 22, folder 182 (1942-1944).

L’Organisation d’Hygiène de la Société des Nations. Geneva, Société des Nations, 1923.

‘Public Health and Medical Services’. Geneva, LON Archives, Series 21641, 1935-1944, 5 dos., cart 6141.

Vingt-cinq ans d’activité de l ‘Office International d’Hygiène Publique 1909-1933. Paris, Office Internationale d’Hygiène Publique, 1933.

White, N. The League of Nations and the Health of the World. Problems of Peace. Second series. London, Humphrey Milford, 1931.