—Sabers en acció: New ways of thinking about science, technology and medicine.—

The Sabers en acció project is an invitation to a historical journey through science, technology and medicine. It is a collaborative project whose authors explore the possibilities of digital humanities to escape from the received views, both in the medium and in the message, through new protagonists, spaces, objects and problems. It deals with a wide range of disciplines, from astronomy to pharmacy, natural history, physics or medicine, always taking into account their transformations and interactions. We aim to offer popular narratives soundly grounded in the most recent historical research, so encouraging more specialised investigations into these subjects. The entries are written by a large team of research staff and teaching staff from the Institut Interuniversitari López Piñero and the Societat Catalana d’Història de la Ciència i de la Tècnica, together with teaching staff from other universities and research centres. In total, a team of more than fifty specialists who have worked in different topics, geographical contexts and historical periods, many of them being protagonists in the emergence of new perspectives on the history of science, technology and medicine during the last decades.

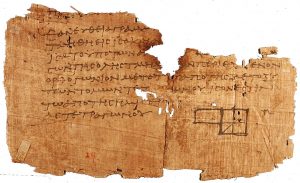

Sabers en acció reviews the different ways in which scientific knowledge has been communicated historically, including media and historical periods as remote as this papyrus with fragments of Euclid’s Elements, which is more than 2000 years old. Wikimedia.

Sabers en acció is based on new trends towards a more inclusive approach to the broad range of ways of knowing across the time and space, including epistemic practices in different societies in the same historical period and the varied forms of interaction. As the historian Peter Burke has pointed out, this perspective implies taking into account knowledge(s) and practices which are usually forgotten in old-fashioned histories of science, technology and medicine, so thinking about the causes of the exclusion. Thus, we review the emergence of knowledge(s) and ignorance(s) as well as their circulation, their unsuspected uses and the resulting transformations. This means placing greater emphasis on the processes of circulation through the use of new scales of analysis, both temporal and spatial. When these new perspectives are adopted, many geographical and temporal partitions considered natural are soon revealed to be part of the prejudices that support hegemonic narratives to the point of making them almost unassailable. Repeated ad nauseam in textbooks, celebrations and other forms of academic liturgy, these narratives permeate a wide variety of discourses that legitimise the exclusion of alternative perspectives, which can only survive in the form of esoteric knowledge or ethnographic curiosities, i.e. they are tolerated to the extent that they retain a limited capacity for action

The intersections between art and science are common in the Sabers en acció journey, as illustrated in this image from the exhibition L’univers à l’envers, Plonk et Replonk, Musée des Confluences de Lyon (2020). Arts in the City.

Sabers en acció project aims not only to study science, technology and medicine in the past. It also aims to restore the agency of historical perspectives in order to think about the present while imagining other futures. A first step is to create the conditions for questioning the dominant narratives through new literary forms, alternative contents and unforeseen angles of perspective. Without ruling out other avenues, this project has explored the virtues of the short story to attack vulnerable points in the received narratives, seeking to challenge hegemonic discourses through guerrilla narrative tactics, through quick and lacerating forays into historical episodes dominated by narratives of great geniuses, turning points, epistemic fables and trajectories of progress. Readers will obtain intellectual tools to think critically about gender biases, Eurocentric narratives, positivistic images, modernity narratives and the relations between knowledge and power. For this reason, many sections are aimed at reconfiguring gazes, reframing scenarios and rethinking the relevance of particular contexts, historical actors and events. Along with subversion and irreverence, Sabers en acció offers materials to think otherwise about science, technology and medicine.

As mentioned above, these issues are dealt with in short, self-sufficient stories. All of entries have an extensive bibliography to satisfy the curiosity of the most demanding readers. The blog is organized along two complementary axes: chronological and thematic. The first is made up of fifty short texts organised around the traditional major periods in the history of science, technology and medicine. These familiar coordinates have been chosen for the beginning of the navigation but they immediately questioned, both in terms of the geographical setting and the chronological periods, borrowed from the great narratives that are questioned. Each of the ten historical periods is organized in five short texts structured around particular characters, spaces, instruments or experiments. Intrepid readers can also go through these chapters according to their peculiar itineraries, a pathway which might be even more stimulating for independent and passionate minds, willing to lose themselves in strange territories, outside the tourist guides.

Women have played a prominent role in the history of science that has often been made invisible. Sabers en acció aims to contribute to the visibility of the works carried out by women in science, technology and medicine, such as these chemical analysts at the Dow Chemical Company in the 1940s. Science History Institute.

In this way, one can pass, at the speed of a click, from ancient temples to modern cyclotrons, from the medieval monastery to the molecular biology laboratory, from 16th century cabinets of curiosities to 20th century science museums, from the alchemist’s workshop to the precision instrument maker’s workshop or the modern pharmaceutical industry. The exhibition takes us at a brisk pace through classrooms, hospitals, salons, natural history museums, chemical industries, academies, courtrooms, military centres, amphitheatres, research seminars and other scientific spaces. One can also approach the rich material culture: reagents, stills, dissected animals, microscopic samples, vacuum machines, clinical tests, herbaria, magic bullets, three-dimensional models, bacteria, telescopes, discharge tubes, measuring instruments and a wide variety of standards which invisibly accompanied the broad spectrum of knowledge in action.

History of science can hardly be understood without the material culture and changing spaces where knowledge was produced, taught and communicated. Thus, surprising scientific instruments, such as this Wimshurst machine belonging to the Luis Vives Secondary School in Valencia, are protagonists of the narratives of Sabers en acció. COMIC. Comisión de Instrumentos Científicos.

In addition to the variety of spaces and objects, the first fifty chapters also mobilise an extensive list of more or less well-known personalities. Surprising episodes of famous people such as Aristotle, Pliny, Galen, Galileo, Antoine Lavoisier, Louis Pasteur, Marie Curie and Ignaz Semmelweis are presented. Other little-known figures are also presented, although with a role that is perhaps more relevant to the subjects dealt with: cosmographers such as Rodrigo Zamorano, popularisers such as Jane Marcet, the British physicist Mary Somerville, the Polish doctor Ludwik Rajchman, or the American researcher Frank Oppenheimer, designer of the new science museums of the 20th century, and whose name has been obscured by the fame of his more famous brother. Other characters are as unclassifiable as Francis Galton, an author with a wide range of interests and creations. Needless to say, the chapters mention a large number of women, more or less known and invisible, from Hypatia to Rosalind Franklin, and offer new perspectives to reconsider activities and spaces where many anonymous women produced and mobilised knowledge of all kinds. Not only science figures are in the plot. We have as guess-starts authors such as Friedrich Hölderlin, Gustave Flaubert, Thomas Mann, Wolfgang Goethe, Francisco Goya or Mary Shelley, to begin with. In spite of coming from a world of fiction, they offer very valuable points of view to understand the science, technology or medicine of their time.

The second part of our tour will be thematic and, with an even freer structure, but always through short stories, will present some twenty themes, such as “Science, Medicine and Gender”, “Food and Health”, “Science and Religion”, “The Publics of science”, “Medical pluralism”, “Science and literature”, “Madness, medicine and society”, “Material culture”, “Epidemics in history” or “Environment”, among many others. This is a complementary approach to the chronological one, which will enable comparisons to be made, gaps to be filled and the biases left by the great periods of traditional narratives to be considered. Two additional sections are at work: an historiographical part and another one covering particular cases.

The chronological and thematic journey begins with this first entry.

Have a good trip! Bon voyage!

José Ramón Bertomeu Sánchez

IILP-UV

How to cite this paper:

Bertomeu Sánchez, José Ramón. Presentation: A chronological journey. Sabers en acció, 2020-11-02. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/presentation-a-chronological-journey/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Manuals

Fara, Patricia. Science: A Four Thousand Year History. OUP Oxford, 2006. (trad. cast. Barcelona: Ariel, 2009)

Lightman, Bernard V. (ed.) A companion to the history of science. Chichester, UK : John Wiley & Sons ; 2016.

Pestre, Dominique et al. (eds.) Histoire des sciences et des savoirs. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2015.

Porter, Roy et al. (ed.) The Cambridge History of Science. Cambridge: Univ. Press; 2003-2018.

Historiography

Burke, Peter. What Is the History of Knowledge? Cambridge: Polity; 2015.

Burke, Peter. «History of Knowledge. A Response». Journal for the History of Knowledge 1, (2020): 7.

Delbourgo, James. «The knowing world: A new global history of science». History of Science, 2019.

Gavroglu, Kostas. O Passado das Ciências como História. Lisboa: Porto Editora, 2007.

Golinski, Jan. Making Natural Knowledge. Constructivism and the History of Science. Cambridge: University Press; 1998.

Govoni, Paola. Che cos’è la storia della scienza. Roma: Carocci; 2018.

Joas, Christian, Fabian Krämer, y Kärin Nickelsen. «Introduction: History of Science or History of Knowledge?» Berichte Zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte 42, n.o 2-3 (2019): 117-25.

Kragh, Helge. An Introduction to the Historiography of Science, Cambridge, University Press; 1982 (trad. cast. (Grijalbo, 1987).

Krige, John, ed. How Knowledge Moves: Writing the Transnational History of Science and Technology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2019.

Oreskes, Naomi. Why Trust Science? Princenton: PUP; 2019.

Pestre, Dominique. Science, argent et politique. Paris: Editions Quæ ; 2003 (trad. cast. Buenos Aires, 2005 / cat. Obrador Edèndum, 2008).

Romano, Antonella. «Making the History of Early Modern Science: Reflections on a Discipline in the Age of Globalization». Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales: 70 (2015): 307-34.

Rossi, Paolo. Las arañas y las hormigas. Barcelona: Crítica; 1990.

Schaffer, Simon. «Les cérémonies de la mesure». Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 70 (2015): 409-35.

Internet resources

Bertomeu Sánchez, José Ramón (ed.) Una introducción a la historia de la ciencia, la tecnología y la medicina. Available at this link.

Daston, Lorraine. The Future of the History of Science: What isn’t the History of Knowledge?, 2018. Available at this link.

Institut Interuniversitari López Piñero. Available at this link.

Societat Catalana d’Història de la Ciència i de la Tècnica. Available at this link.