—Born at the end of the thirteenth century, anatomical dissection went from being a sporadic rarity to a widespread experimental practice in Western scientific culture.—

The opening of a cadaver with the aim of searching inside it to learn the composition and structure of the human body was a practice that originated in medieval universities in Italy towards the end of the thirteenth century and was associated with the reading of Galen’s texts on anatomy. In the same period, perhaps even earlier, the expert examination of corpses suspected to have been victims of a crime or to have died due to some illness liable to become an epidemic began to proliferate. Most of the time, these examinations involved the total or partial opening of the body and were carried out by one or more surgeons by order of the courts or government institutions. Finally, it was also then that certain traditional practices related to the manipulation of corpses in the religious rites of Christianity (embalming, dismembering to obtain relics, examining remains in relation to miraculous beliefs or processes of beatification, etc.) gradually spread in both the south and west of Europe.

Andreas Vesalius dissects a woman’s corpse in Padua (De Humani Corporis Fabrica, Basilea, 1543). Wikimedia.

Opening, cutting, separating tissues and organs in corpses has since then become an activity going far beyond the purpose of demonstrating a reading of a classical text in the lecture theatre, directed by and for physicians. Although, undoubtedly, anatomy in the university context became an essential aspect, the impact and effects of practices associated with the manipulation of cadavers went beyond the strict professional world of physicians. In fact, they were used to strengthen philosophy, theology, jurisprudence and art, apparently unconnected areas – according to our current system of knowledge – but which, in the centuries of the so-called first modernity, were not only contiguous, but also integrated into the same academic culture.

A cultural practice as such, complex and plural in its uses and meanings, public anatomical dissection was not the brilliant invention of a single figure. Even so, as so often happens, the history that most of us have been told follows a rigid script with a male protagonist, a simplified history of ‘discovery’ expressed in the narrative of the misunderstood defence of the truth against the hostility of everything and everyone else. The culmination of the fable is the final victory of the intrepid figure, generally posthumously, when a handful of followers spread the new truth throughout the globe. Outlined in this way, the strong Christological or evangelical parallelism of such a model will escape no one.

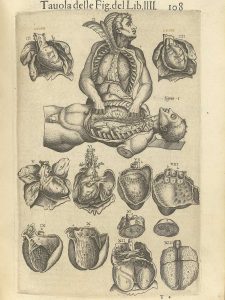

El anatomista anatomizado. Engraving of the Anatomia del hombre by Juan Valverde (Roma, 1556). National Library of Medicine.

According to the canonical narrative of the history of science, scientific truth began to triumph (in this case, over medieval medicine, supposedly immersed in ignorance and darkness) when the Flemish Andreas Vesalius stepped down from his university chair, went down to the centre of the anatomical theatre in Padua, knife in hand, and opened a cadaver before his attentive and astonished students to explain that what they were going to see, inside that body, showed that what Galen’s books said about human anatomy was not true. Against all odds, against prohibitions and censorship, the force of truth prevailed and Vesalius triumphed. This epic rhetoric is based, as usually happens in these cases, on an intentional selection of elements that comply with the historical reality of that moment and the consequent concealment of others. The glorification of Vesalius as the ‘inventor’ of ‘modern’ anatomy is inherent to the origins of the history of medicine as an academic discipline for the teaching and training of physicians in the second half of the nineteenth century. Such an invention is based, among other things, on an effective use of the powerful image on the cover of his most famous book, De humani corporis fabrica (On the Structure of the Human Body) as well as of some of the expressions with which Vesalius himself did not hesitate to promote himself in the heated debates with his Parisian masters. Apart from this, the strength and originality of the engraving are indisputable. The scene is to be understood as representing one of the dissections carried out by Vesalius during his teaching in Padua, in one of those temporary and provisional theatres that were set up for winter anatomical sessions.

John Bannister dissects a corpse at the College of Surgeons in London (anonymous author, ca. 1590). Wikimedia.

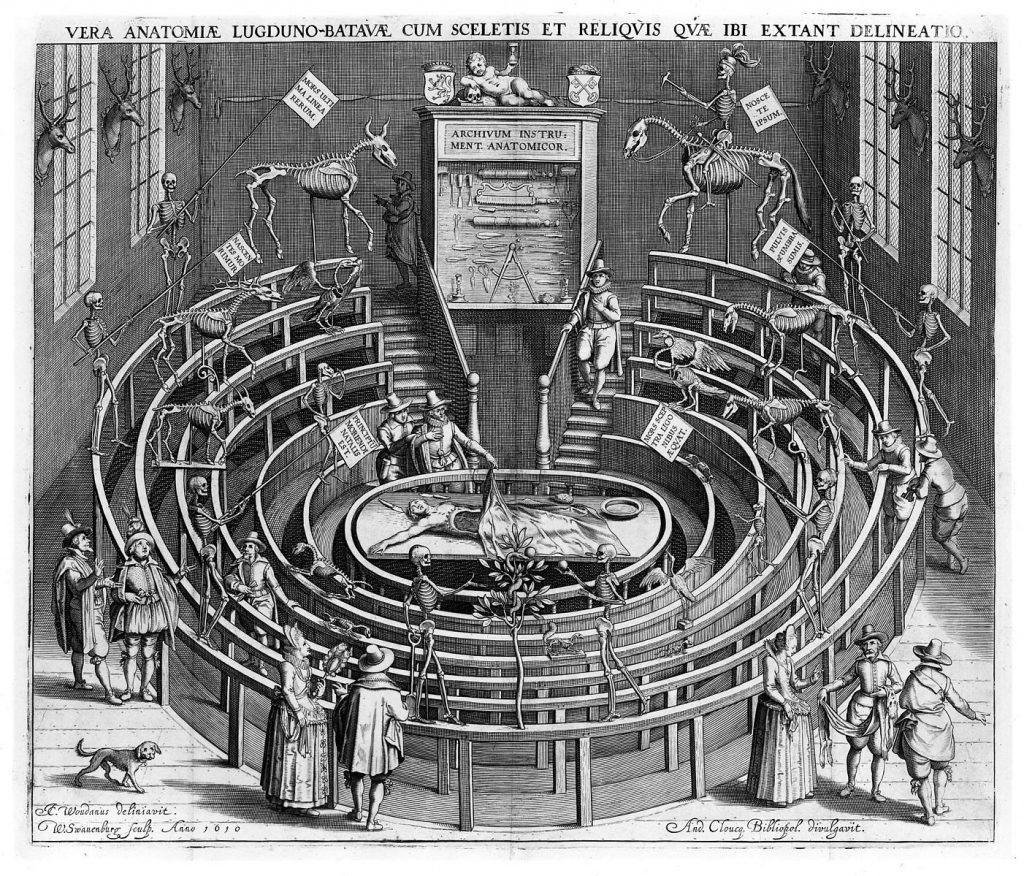

As we have tried to show, the historical reality was much more complex and, of course, much more interesting. Far from the image of ecclesiastical prohibitions advocated by nineteenth century historians (and whose echoes are still repeated in some current misguided proclamations), anatomical dissection became a highly successful event that attracted growing and increasingly diverse audiences. In fact, in the mid-sixteenth century, the unstoppable prestige of anatomy eventually led to the creation of a specific space to house it: the anatomical theatre. A name that indicates not only the structure of the architectural space in question (theatre or, more commonly, amphitheatre) but also the ambivalence between teaching activity and spectacle that anatomical dissection had during that time.

Anatomical theatre in Leiden, after dissection, according to an engraving of 1610. Wikimedia.

The theatre, at first provisional, and then an increasingly common permanent structure over the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, was the space for carrying out that unique public experiment which was anatomical dissection. Physicians and masters of surgery, medical students and apprentices of surgeons, painters and sculptors, bystanders and the general public took part in, saw or discussed what was happening at the dissection table in the theatre. The gradual generalisation of dissections was driven by the existence of these wide ranging audiences, who attended a spectacle that allowed them to lean out from the benches and railings of the theatre, as though it were from a balcony, into that microcosm that was the human body, that almost perfect work of divine creation like the macrocosm of the earth, the moon and the other celestial spheres.

Rembrandt, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, before the college of surgeons in Amsterdam (1632). Wikimedia.

From the dissection table, the participants and the audience of the anatomical theatre projected themselves onto other mental domains, permeating a whole specific way of perceiving and understanding nature and the organisation and functioning, not only of the human body, but also of the social body and the entire universe. As the title of a fascinating book by Rafael Mandressi suggests, the anatomist’s gaze invented more than they discovered in the human body; it was an observable and tangible reality, of course, but with which, to a great extent, an original and complex intellectual artefact was built: a body conceived as a microcosm, as the correlate of the universe, of the macrocosm, on a human scale. We must not forget that the ultimate purpose of capturing the deep relationship between macro and microcosm was to know and admire the work of a Supreme Maker, whose existence was not only not questioned, but reaffirmed. The connection between dissection and human admiration for divine creation is undeniable in the writings of anatomists, in the iconographic representations of dissections, as well as in the ceremony surrounding public anatomical dissection itself. Furthermore, it was this success that legitimised the great anatomical discoveries of the period that made the enormous growth of morphological knowledge about the human body possible, as well as the emergence of systems explaining its origin, development and functioning, which were increasingly distant from the old Hippocratic-Galenic system. Therefore, the basis of most of the medical controversies that proliferated over more than three hundred years was the stream of new ideas coming from the dissection table, the unique experiment that was anatomical dissection.

José Pardo Tomás

IMF-CSIC

How to cite this paper:

Pardo Tomás, José. Opening cadavers, a unique experiment. Sabers en acció, 2020-12-04. https://sabersenaccio.iec.cat/en/opening-cadavers-a-unique-experiment/.

Find out more

You can find further information with the bibliography and available resources.

Recommended reading

Carlino, Andrea. La fabbrica del corpo. Libri e dissezione nel Rinascimento. Turin: Einaudi; 1994.

Cunningham, Andrew. The Anatomical Renaissance. The Resurrection of the Anatomical Projects of the Ancients. Aldershot: Scholar Press; 1997.

Mandressi, Rafael. La mirada del anatomista. Disecciones e invención del cuerpo en Occidente. Mexico: Universidad Iberoamericana; 2012.

Studies

Andretta, Elisa. Juan Valverde, or Building a ‘Spanish Anatomy’ in 16th Century Rome, Florence: EUI Working Papers; 2009.

Ferrari, Giovanna. Public Anatomy Lessons and the Carnival: the Anatomy Theatre of Bologna; Past and Present, 117, 1987: 50-116.

Klistenec, Cynthia. Theaters of anatomy: students, teachers, and traditions of dissection in Renaissance Venice. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2011.

Mandressi, Rafael. Affected Doctors: Dead Bodies and Affective and Professional Cultures in Early Modern European Anatomy. Osiris, 31, 2016: 119-136.

Park, Katharine. Secrets of Women. Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection. New York: Zone Books; 2006.

Schupbach, W. The Paradox of Rembrandt’s ’Anatomy of Dr. Tulp’. London: Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, 1982.

Skaarup, Bjorn. Anatomy and Anatomists in Early Modern. Spain. Farnham: Ashgate.